40 Years of BC Libraries Through the Eyes of a Cataloger

Chris Conroy just retired after a transformative career at BC Libraries in which she started as a cataloger and finished as Associate University Librarian for Collection Services. This article is based on some of her recent reflections about the changes her career spanned.

Dropping the Card

If you ask a cataloger, the only reason libraries work is accurate cataloging: if our resources weren’t organized, you’d be hard-pressed to find anything. So if you want to understand what’s under the hood of the BC Libraries website, you have to learn a little history about the transition from card catalogs to computer catalogs & the changes that followed. Chris Conroy started her BC career on the cusp of that moment.

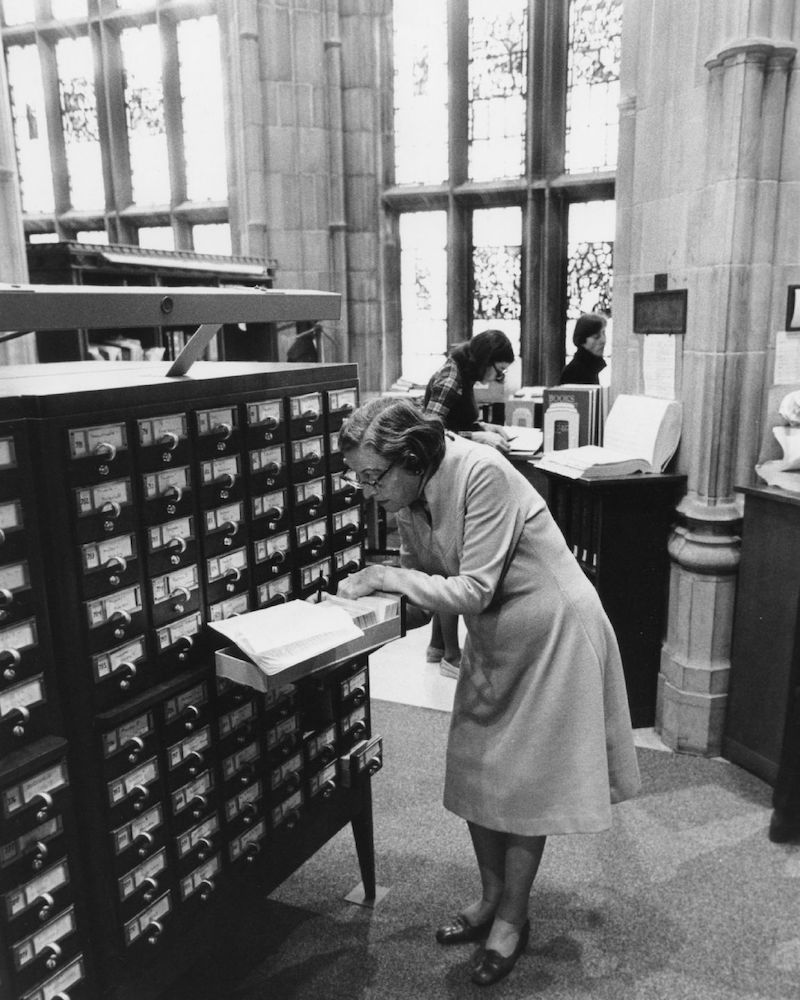

In 1980 when Bapst was the main library and some of the latest technology–six idle computer terminals and a dot matrix printer–occupied what is now the Burns Irish Room, and the office of the head of cataloging was where a coat-rack now stands, a new cataloger had to pass a typing test. Part of the job of a cataloger was typing bibliographic information–what librarians now call metadata–onto cards for the catalog. That’s the way it had been done since the early 1900’s (Book at BC Libraries). Picture the Burns Reading room as a warren of desks with typewriters. When Chris Conroy arrived at BC Libraries as a cataloger in 1979–just three years after the first computer terminal was installed in the Library of Congress Reading Room–she had an inkling things would be changing.

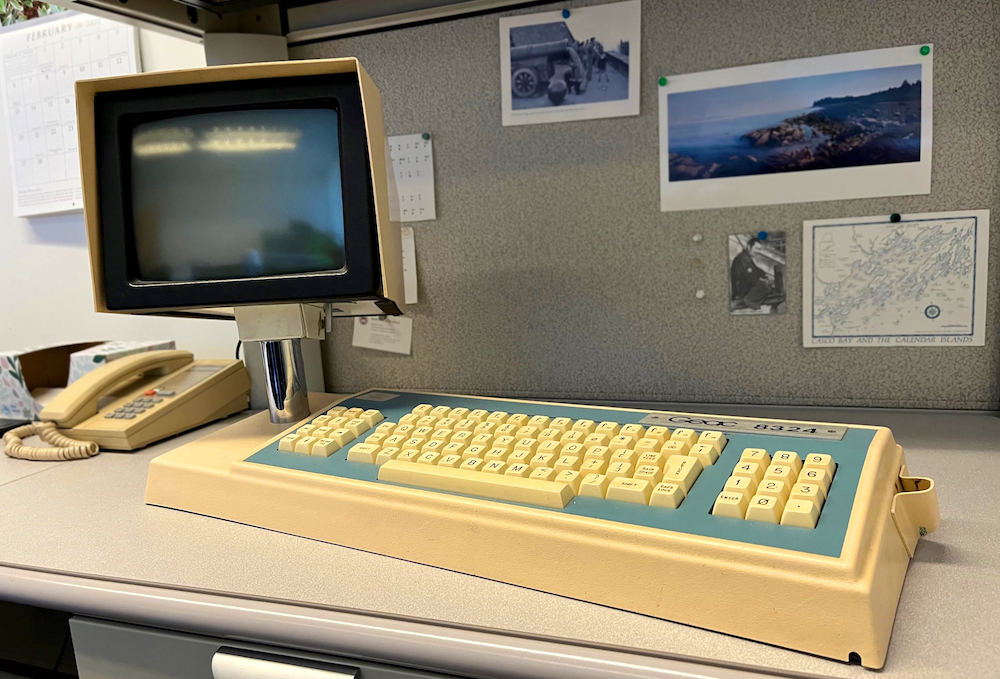

At the time, though, in the early 1980’s, technology had such a hard time altering hidebound cataloging practices that Chris had to lobby for catalogers to be included in professional development involving technology. She knew the computer terminals wouldn’t be idle for long. Large tape reels full of cataloging data were stacking up next to the terminals, and it would only be a matter of time before their contents would change everything.

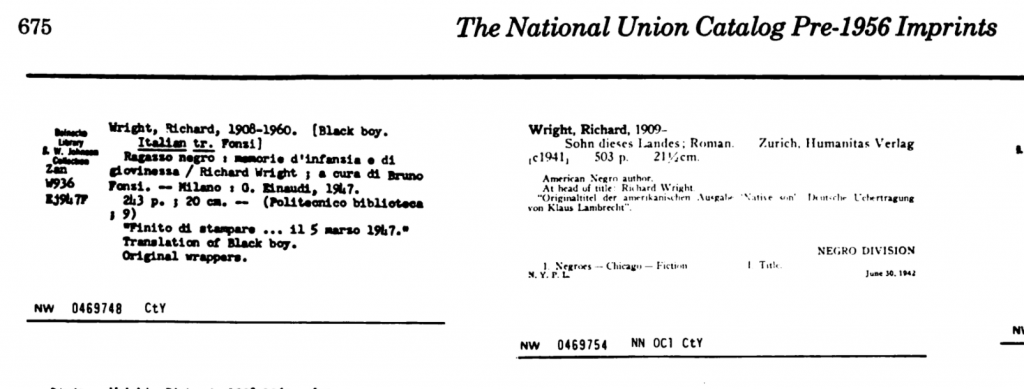

Cataloging technology circa 1980: a Polaroid camera and an electric eraser. Cataloging staff used a specialized Polaroid camera to take photos of records in the National Union Catalog published by the Library of Congress, and created new catalog entries from them. Chris said she can still recall the acrid smell of the fixative they used to preserve the Polaroid images, otherwise apt to fade. The electric eraser was for correcting mistakes on catalog cards. The process went like this: a copy cataloger would type a card based on the cataloger’s research (or just pull a pre-printed one shipped from the Library of Congress), then file it in the catalog “above the rod” (literally, the metal rod that went through a hole at the bottom of each card to keep them in order). A higher-ranking cataloger (a librarian with a library science degree, such as Chris) would then approve the placement by “dropping the card” onto the rod.

Early Adopters

O’Neill Library opened in 1984, only a few years after Chris’s arrival. Along with the move into the modernist building (designed by students of Walter Gropius), the Libraries moved all of the card catalog records into a new computer system called Geac, adopted only a few years before both by the Library of Congress and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. (Chris missed out on the move by working across the river at Harvard for a few years.)

But Geac had some problems, which had three results, all byproducts of an early transition from analog to digital: One, to provide an alternative to inconsistent records in the computer system, the massive old card catalogs were moved from Bapst to O’Neill, where they sat for close to a decade on level two on the current site of the CFLC. Two, the Geac system was replaced in yet another complex transition only a few years later by NOTIS (a system also adopted by Harvard at the same time). Three, some of Geac’s problems affected the cataloging data that was transferred to the new system, and even though BC Libraries has transitioned through three library management systems since, staff still occasionally run across remnants of those early problems, said Kathryn Doan and Meg Critch, Senior Metadata and Systems Librarians.

The nineties, said Chris, saw many additional changes, including the automation of print periodicals with barcodes, federated searching, and a transition to yet another library management system and online catalog, this time accompanied by a contest to name it. (The winning name: Holmes.) Chris was also promoted to Head of Cataloging. But all of these changes, as impactful as they were to library patrons and staff, would be dwarfed by what seemed a molehill in the late 1990’s: Science Direct began to offer electronic versions of articles, and also a deal bundling many journals together in one subscription.

The Big Deal

In the early aughts, a few other publishers followed Science Direct’s lead and started offering e-journals as free add-ons with print journal subscriptions. Within a few years, though, that equation flipped: free print subscriptions were offered along with e-journal subscriptions, driving the proportion of e-journals yet higher.

Periodicals catalogers faced problems on two fronts: one, the whole process of adding journals went from a linear series of steps to everything happening simultaneously. Two, in spite of selling an increasing flood of e-journals, publishers developed no tools for libraries to organize and catalog them. Whole departments were re-organized around new processes, and staff created home-grown relational databases to track subscriptions.

By the middle aughts, the balance between print and online journals had shifted dramatically, from 20% electronic to 80%. Along with that shift more publishers began to offer bundles of e-journals rather than individual titles, an arrangement librarians now refer to as The Big Deal.

It was around the beginning of this major transformation that Chris became the AUL for Collection Services, so she had a front row seat to the dramatic impact on the BC Libraries budget. Before the proliferation of e-journals, said Chris, librarians could count on a 60:40 ratio of one-time purchases (in other words, books, a.k.a. monograph), to continuing purchases–periodicals and indexes. In 2022 that ratio is more like 10:90. All academic libraries are encumbered this way, with annual subscription prices taking up the majority of spending and reducing budgeting flexibility. Hence, the big drive for Open Access journal publishing: to reduce the ballooning prices of journals (and of course to broaden open access to information).

Chris was hard-pressed to identify anything that didn’t change throughout her many years here. A good many people have been around for a long time, she said, like Delia Duart, Senior Continuing Resources & Cataloging Assistant, who pre-dated her tenure, and George Malcom, Senior Cataloging Assistant, who arrived shortly after her, but changing systems always meant changing work relationships. You might work with someone for several years, then the process and organization would change, and you’d work with new people and do new things. The only constant is adapting. George agreed, and even speculated that we could adopt a new system someday soon, and everything would change yet again, but having worked through many such changes he was philosophical about it. “It keeps it interesting.”

What’s next for BC Libraries? Chris said with a smile, “I’m retiring; it’s no longer up to me.” But she had this advice from long-time colleague and (retired) head of collections Jonas Barciauskus: “It pays to remain light on our feet.”