First Peoples in Children’s Literature

This weekend, Boston College recesses for Fall Break, and on Monday, everyone will enjoy a public holiday. While the university officially observes Columbus Day, many community members prefer to honor Indigenous Peoples’ Day, in recognition of the First Peoples who have made great contributions to this nation’s history, and whose roots are much deeper than 1492 when Columbus first made contact in the New World. The terrible ramifications of European contact in the New World for many of the First Peoples also deserves recognition.

At the Educational Resource Center, where we support the needs of the Lynch School of Education and its social justice mission, we recognize that the First Peoples play a role not only in how we remember the first European contact with the New World, but in how we remember the first Thanksgiving.

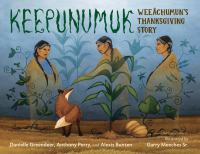

Fortunately, in recent years, there has been a trend in children’s publishing around the Thanksgiving holiday towards teaching critical history. One great picture book to share with students this holiday season is Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story (2022) available at the ERC. Weeâchumun means corn in Wôpanâak, the language of the Wampanoag people who lived at Plymouth where the settlers we know as the Pilgrims landed, near where the federally recognized Mashpee Wampanoag and Tribe and Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head still live.

Keepunumuk tells the story of the first Thanksgiving from the Native perspective, and also incorporates the perspectives of plants and animals such as the seagull who first spots the “newcomers” and the corn, beans, and squash or “three sisters” who send dreams to the First Peoples with a message, asking that they extend their hospitality to the hungry white settlers, and teach them how to use the land they share in order to feed themselves. This technique of giving voice to other species emphasizes the rootedness of the First Peoples, as well as their landedness, their spirituality, and their deep scientific knowledge of the natural world.

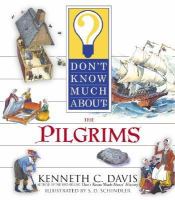

Of course, the story culminates with the feast we all remember, but not without the reminder: “Many Americans call it a day of thanksgiving. / Many of our people call it a day of mourning.” Such an ending marks a pronounced contrast between new books such as this one, and older ones in our collection such as Don’t Know Much about the Pilgrims (2002), which closes with the question “What happened after the Pilgrims’ Thanksgiving party?” and neglects to mention how the “Indians” it depicts faced disease and violence during the era of colonization that actually followed the first Thanksgiving.