Copyright & Copying

When was the last time you made a copy of something? Maybe you photocopied a few pages out of a book for a class, or used a picture you found online in a presentation. Maybe you’ve seen some intimidating warnings about how large the penalty for violating copyright can be, and decided not to make a copy of something that would be truly useful. That would be unfortunate – you don’t need to be afraid of copyright law, you just need to be thoughtful about it.

Copyright is a Balancing Act

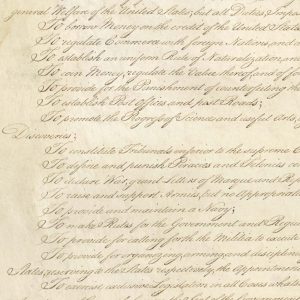

On the one hand, the restrictiveness of copyright law serves a useful purpose. In theory, it incentivizes people to create more great content. Without copyright protection, it could be hard (or even harder) to make a career of writing or filmmaking, for example. On the other hand, copyright law in the United States is based on the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8), which allows Congress to grant creators exclusive rights to their work, but only for a limited time, “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”

How do we resolve the tension between the exclusive rights of creators and intellectual progress, where advancements are built upon the works of other people? The answer is fair use.* Fair use can apply when copying a work for criticism, comment, news reporting, scholarship, or research.

Fair Use Factors

But how can you tell if your copying is fair use? There is a balancing test of four factors that a court considers. They are:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

There is no use that is automatically a fair use, even for non-profit organizations or educational purposes. However, that type of use is quite favorable to a finding of fair use under the first factor. The fourth factor is also quite important. Consider if the copy can replace the original for someone looking to buy or access the copied work. The more a copy serves as a replacement, the less likely it is to be fair use. One would not need to quote an entire chapter while writing a book review, but may need to quote specific passages. Even copying an entire book to use it in a search engine has been found to be an example of fair use, with the amount copied not being automatically disqualifying, because it doesn’t negatively affect the book’s market value. If any of this is confusing, feel free to contact me: elliott.hibbler@bc.edu.

Digging Deeper

Every fair use analysis starts with these factors. However, there is no simple algorithm to give a quick “Yes” or “No” to the fair use question; this is a balancing test performed by judges in each case.. In your fair use analysis, one resource to consult is our Copyright and Scholarship Guide. If you have the time and energy to look at case law check out the Fair Use Index from the U.S. Copyright Office, which makes it easy to look up what courts have done in other fair use cases. Seeing how courts treated similar situations is the most accurate way to figure out if a use is likely fair. These are just case descriptions, with key facts, the case outcome, and a holding, which summarizes the reasoning behind the case outcome. To find the full text and other material about the case, check out our Researching a Legal Topic Research Guide. No matter how fair your copying may be, there is always an option to avoid fair use entirely. If you know who the copyright holder of a work is, you can always ask for permission to make a copy.

Finally, don’t forget that even if you are not copying something word-for-word, or pixel-for-pixel, you still need to attribute the creator appropriately, with proper citation for your discipline!

*Another acceptable answer would be “limit the length of copyright to an actually reasonable period” rather than terms that can extend more than 100 years, but that is a topic for another day.