Urban Activist

Jacobs did not regard herself as an activist, but as a thinker and a writer. Yet she did wear the badge and earned her stripes: she organized and led mass protests against urban renewal and expressway projects as well as the Vietnam War, got arrested, and got results.

While Jacobs was writing Death and Life, the forces of urban planning that she was critiquing took direct aim at her own neighborhood. In 1961, New York City’s planning commission designated the western district of Greenwich Village as a target for urban renewal. Jacobs knew that meant her neighborhood would be demolished and replaced with larger, sterile structures. She quickly organized the Committee to Save the West Village, which proposed an alternate and ultimately successful plan to add dwelling units through the renovation of existing buildings at a lower overall cost.

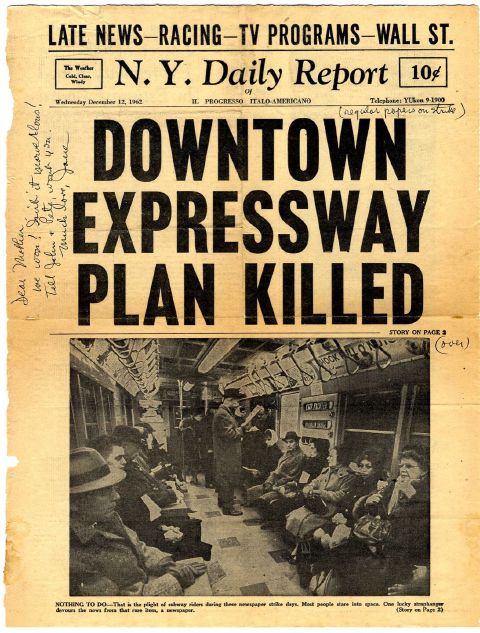

Robert Moses, New York City’s “master builder,” also proposed to funnel an expressway through Lower Manhattan. Sections of Soho, Little Italy, and Chinatown would be sacrificed. Jacobs assembled and chaired a coalition committee to fight the project, beating back Moses’s attempts to push it through the city planning commission for more than a decade, dealing it a death blow at a hearing held on April 10, 1968. A large crowd turned out and began chanting “We want Jane!” When she was finally given the microphone, she called other protestors to the platform. Some claim that she tore up the stenographer’s notes so that there would be no official record. Regardless, she was arrested for disorderly conduct, a charge that was eventually dropped. Subsequent newspaper stories turned the mayor and city officials definitively against the expressway, which was quietly abandoned in future city plans.

Meanwhile, protests were mounting against the Vietnam War. The Jacobs, who had two draft-age sons, packed the family car and scrambled up to Canada. The house they rented in Toronto turned out to be in the path of another proposed urban expressway. Jacobs mobilized once again, and helped to lead a successful challenge, getting herself arrested twice during demonstrations.

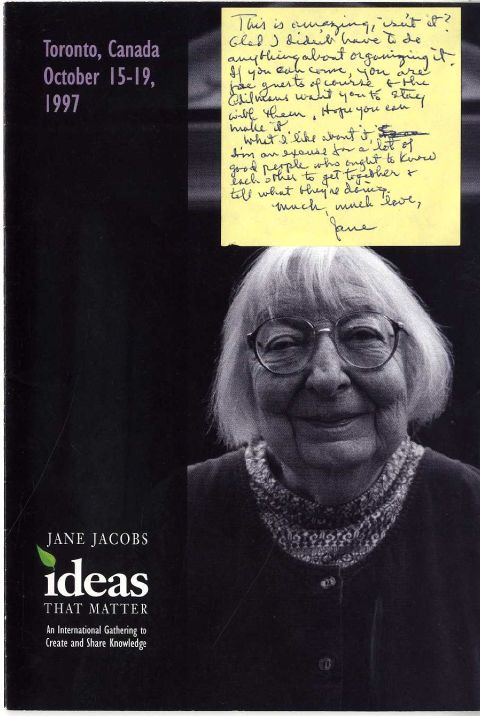

Jacobs also influenced the regeneration of Toronto’s St. Lawrence neighborhood. It may seem ironic that the author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities should give up her citizenship to become a Canadian. Yet Jacobs was quickly adopted by her adopted country. Within a year of her arrival in 1969, she was invited to give the annual Alan B. Plaunt Memorial Lecture at Carleton University. In her address, she cited Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, whom she had befriended, observing that America acts as Canada’s “built-in Early Warning System” for urban problems. She became a Canadian citizen in 1974. In 1997, Toronto hosted a 5-day international symposium to stimulate discourse and debate around issues relevant to cities and the values of diversity, community and the public good—ideals championed by Jacobs. A book and an annual prize named in her honor were the results. Jacobs sent a copy of the program to a friend with a Post-it note, remarking: “This is amazing, isn’t it? Glad I didn’t have to anything about organizing it.” For once the intrepid community mobilizer got a bye. She was invested as an Officer of the Order of Canada the following year, and was awarded the Order of Ontario in 2000.

After Jacobs’s death in 2006, friends decided that instead of advocating for a park or street to be dedicated in her name, it would be more in keeping with her ideals to encourage people to become more familiar with streets in their own neighborhoods by walking them. Every year around Jacobs’s birthday on May 4, “Jane’s Walks,” as they are called, are hosted by volunteer individuals and organizations. So far, more than 200 cities in 40 countries have participated.