Short Stories

Pulp Fiction?

Until the publication of The Short Fiction of Flann O’Brien in 2013, O’Nolan’s reputation rested primarily on his novels and newspaper columns. Yet over the course of his life, he wrote a dozen or so short stories in both Irish and English, publishing them in a range of periodicals, from student magazines to Irish, British, and American literary reviews, using a variety of pen names in addition to his own.

A story titled “I’m Telling You No Lie!” is attributed to Lir O’Connor, a pseudonym O’Nolan used to impersonate playwright Frank O’Connor in their scurrilous exchange of letters in The Irish Times. Scholars are still debating whether the “John Shamus O’Donnell” who contributed a humorous science fiction sketch to the winter 1932 issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly might have been a certain precocious University of Dublin student.

Banned in Dublin

“John Duffy’s Brother,” a tale about a man who thinks he is a train, combines steam punk and surrealism. O’Nolan wrote and published it right around the time he was working on The Third Policeman, whose similarly nameless protagonist also suffers a crisis of psychological identity.

The story first appeared in the June 1940 issue of Irish Digest with a byline indicating that it had been aired on Radio Éireann. The following year it was published in the New York magazine Story. It both instances, Flann O’Brien is given as author, but there is a subtle yet significant difference between the two printings.

The American version restores a detail in the description of a family relation of the main character, who is said to have joined the merchant marine at age sixteen “as a result of an incident arising out of an imperfect understanding of the sexual relation.” Bowing to the censorial regime of the Irish Free State, the Digest editors had softened the portrayal of the circumstance, altering the line to read “an incomplete knowledge of the world.”

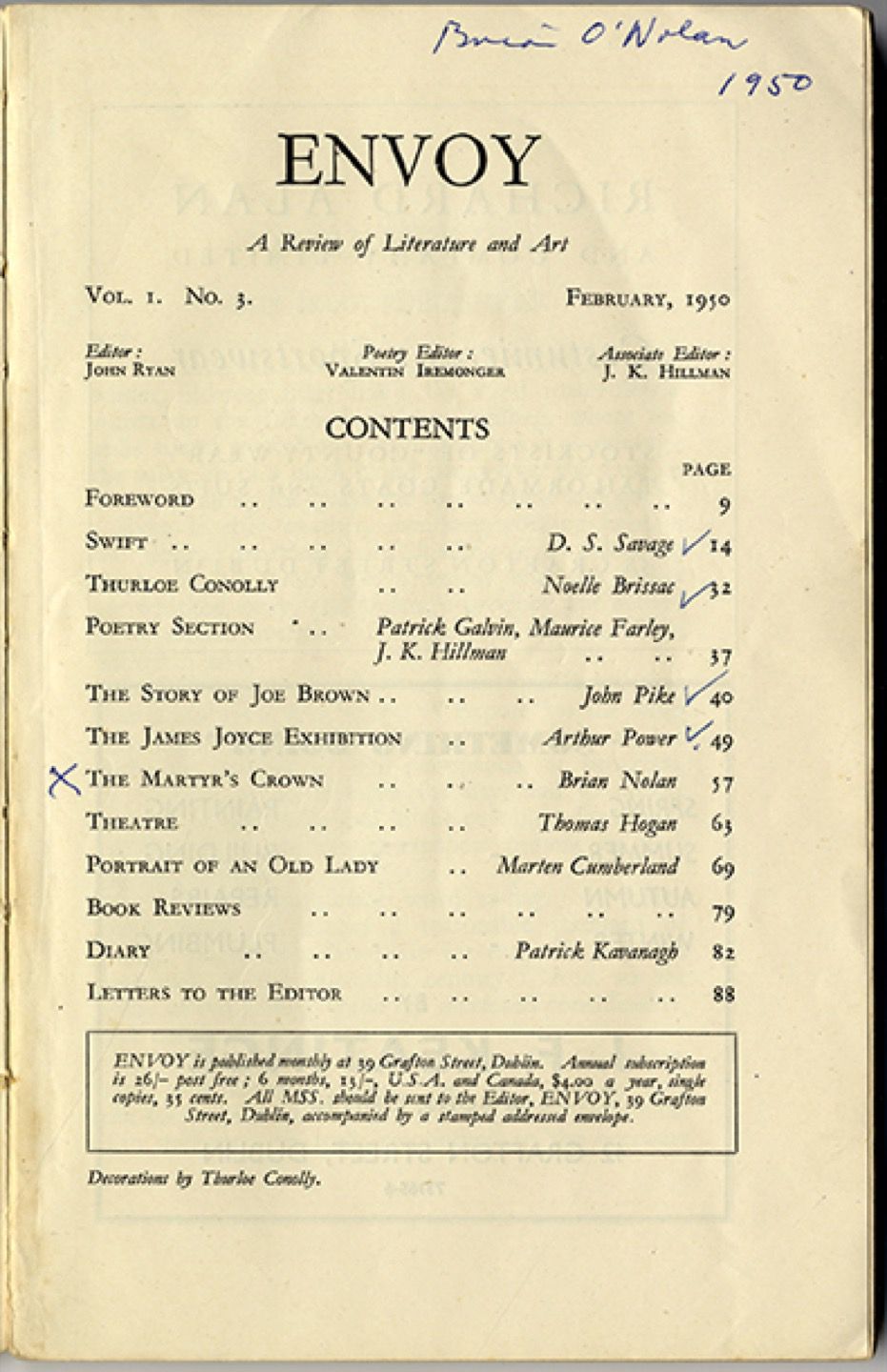

Envoys

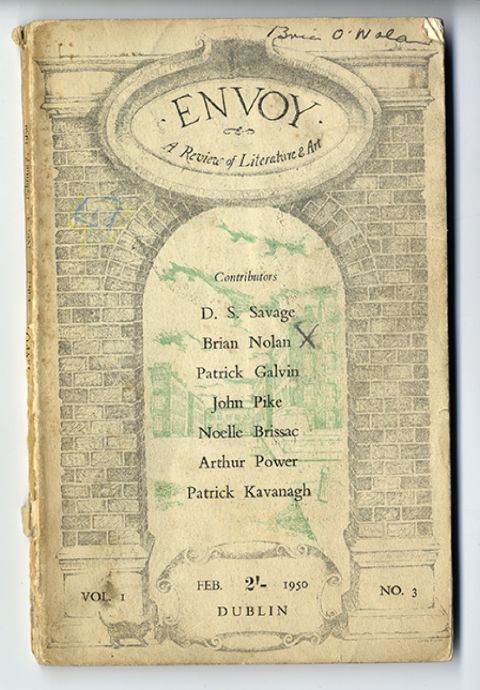

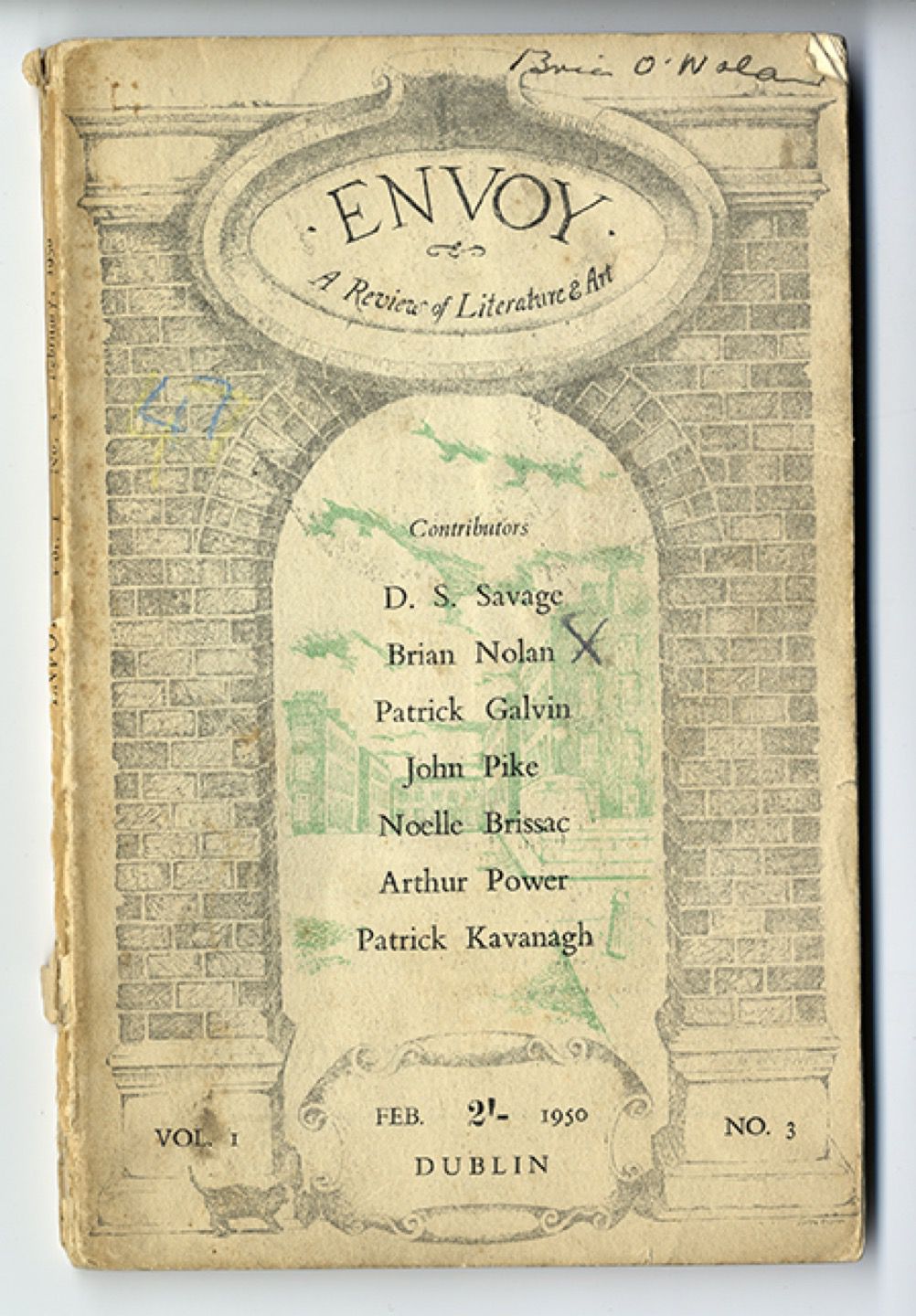

John Ryan was a Dublin painter, publican, and one-time publisher who launched a monthly review of literature and art in December 1949, just as Ireland was becoming a fully independent republic. He hoped it would help overcome the stringent codes and culture of censorship that had been forcing Irish authors to publish in England and abroad. Envoy lasted only two years, but succeeded in showcasing a broad range of talent and styles.

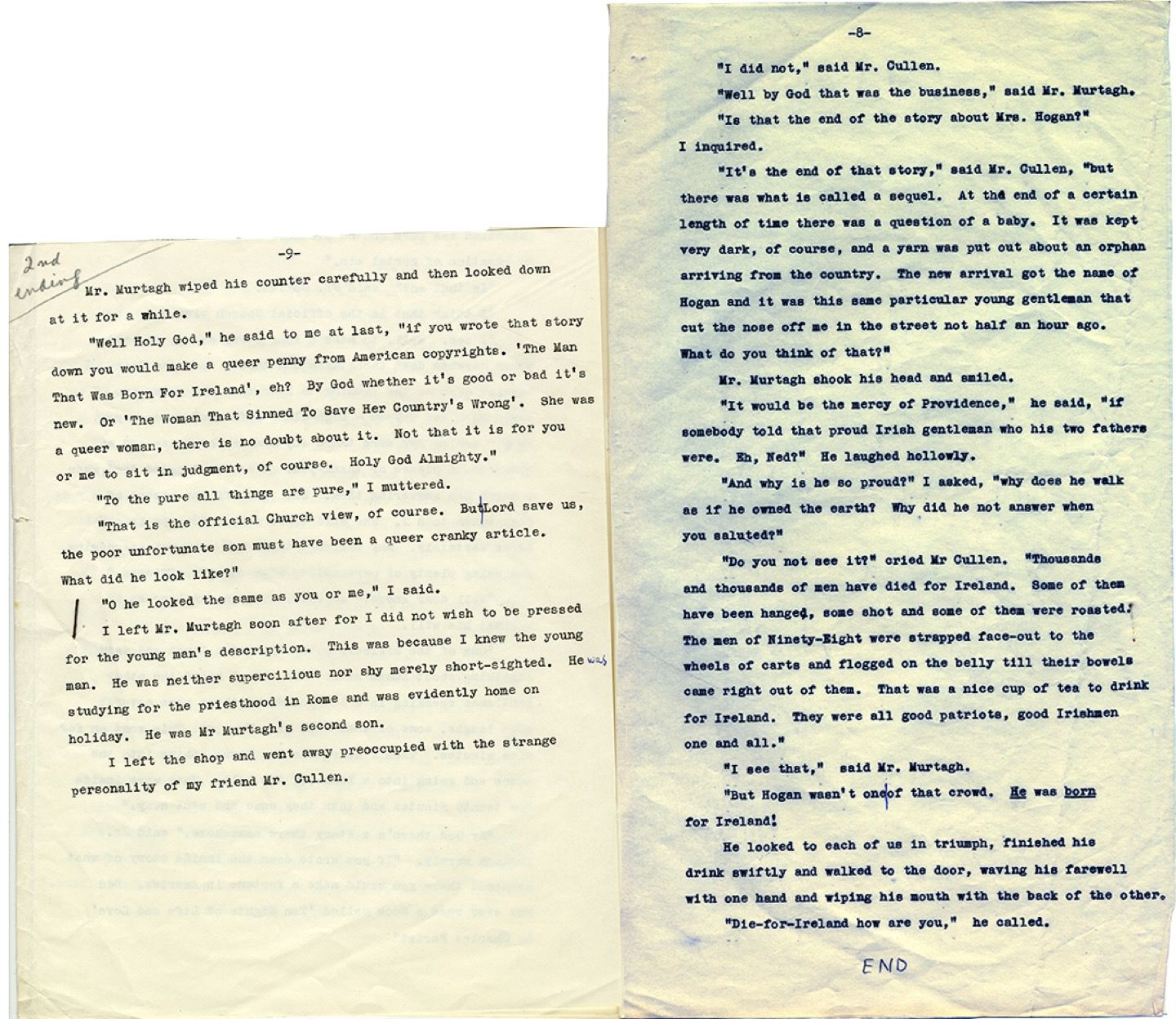

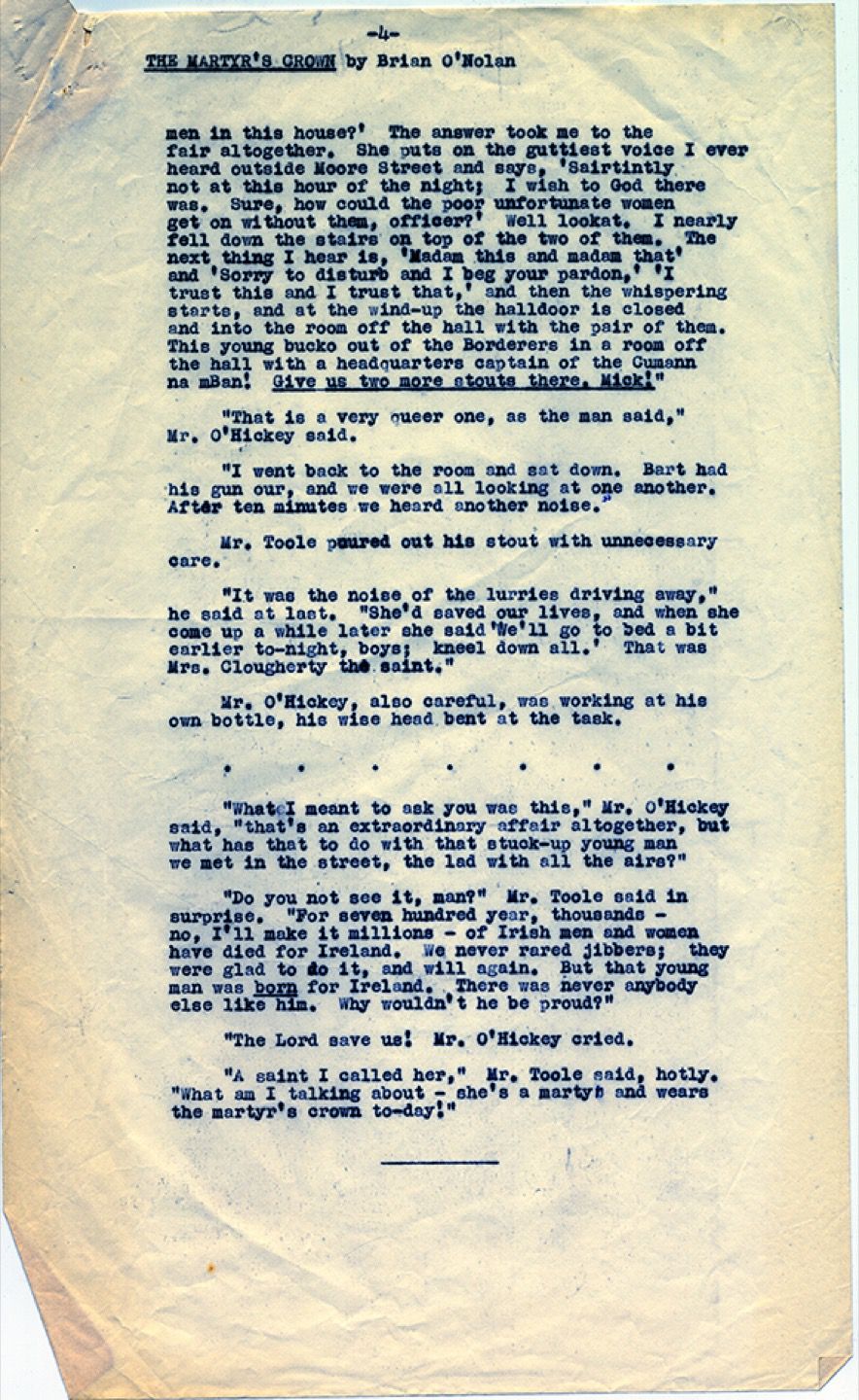

The third issue included a piece by “Brian Nolan” (not “O’Nolan”—an editorial error or pseudo-pseudonym?). Titled “The Martyr’s Crown,” it represented a substantial reworking of an earlier story O’Nolan planned to attribute to Flann O’Brien called “For Ireland Home and Beauty” about a woman who feigned prostitution during the Irish Revolution to protect fighters. O’Nolan experimented with different endings for the farcically subversive tale until settling on the one that yielded the title used in Envoy.

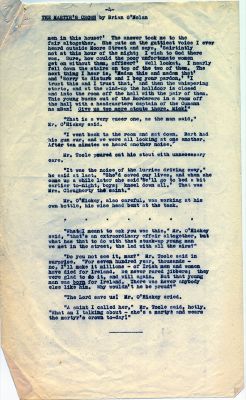

Envoy Title Page

Nolan, “The Martyr’s Crown,” Envoy 1, no. 3 (1950), PR6029 .N56 M37 1950 O’BRIEN LIBRARY

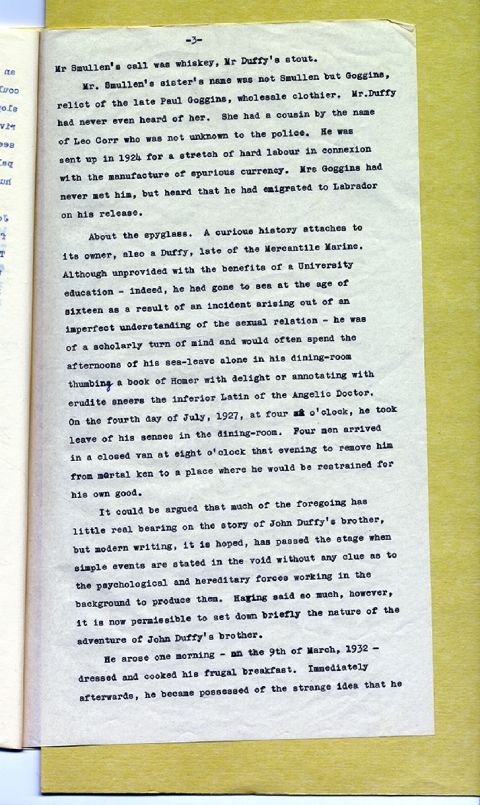

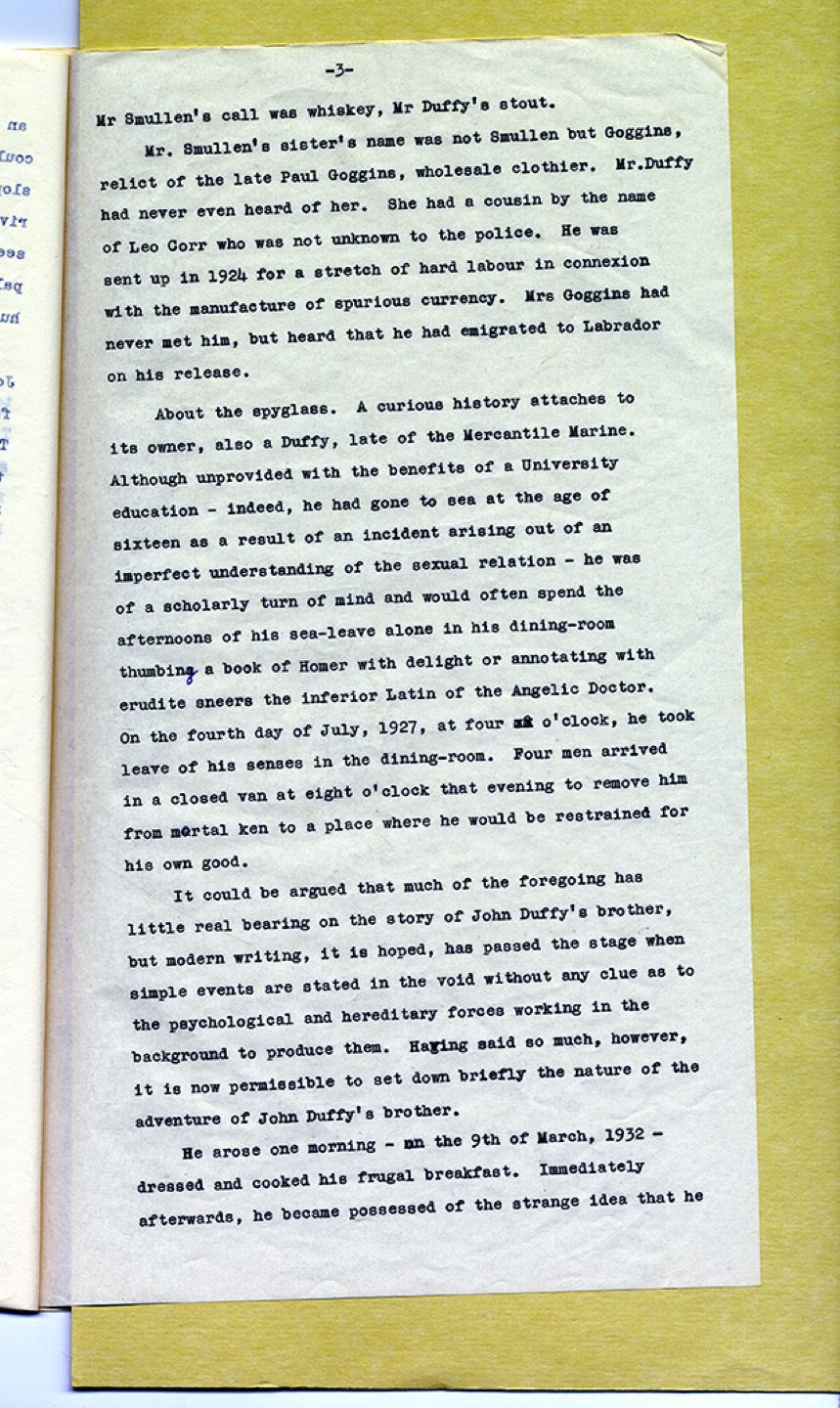

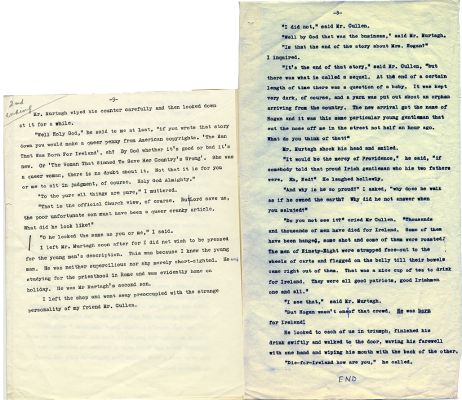

2nd ending, ‘The Martyr’s Crown’

Box 5, folder 15 , Flann O’Brien Papers MS1997-027

Typescript for ‘The Martyr’s Crown’ which has a completely different opening and ending than “For Ireland Home and Beauty”. p. 4

Box 5, folder 15 , Flann O’Brien Papers MS1997-027