Overview

The Ancient City of Selinus

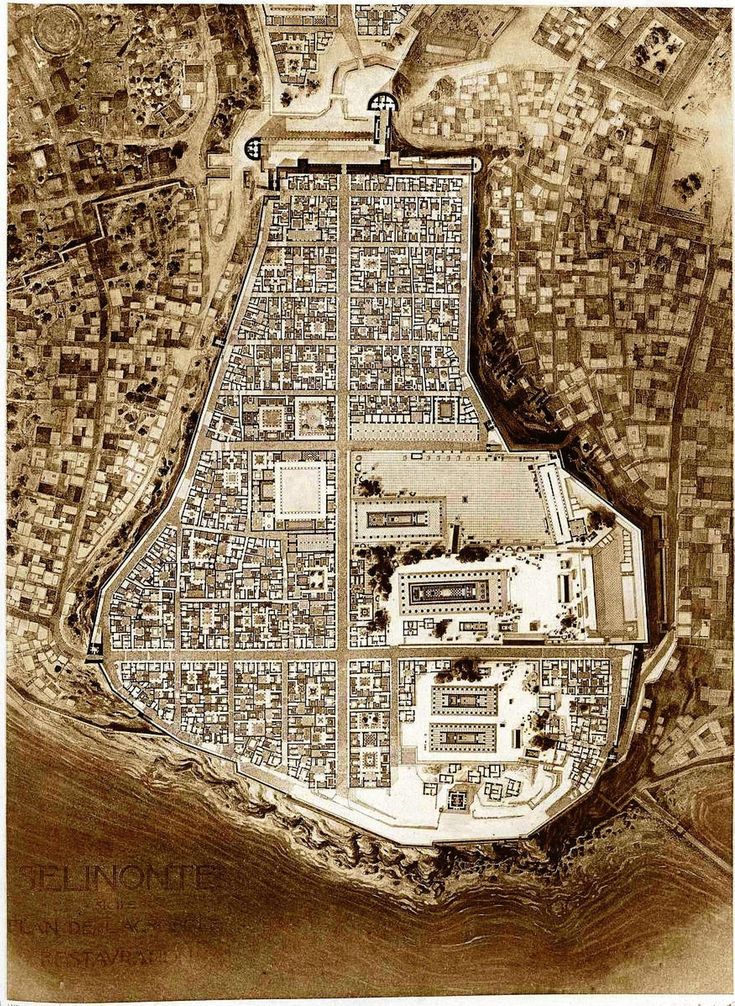

Located on the western coast of Sicily, Selinus was founded by a group of colonists from Megara-Hyblaea and Megara Nisea under the leadership of Pammilos around a century before Temple C’s construction. Although Selinus had a poorly defended position on the coast, as proven by its defeat by the Carthaginians in 409 BCE, it was one of the most powerful Greek colonies. It commanded a large portion of land in western Sicily. There are two arguments for the foundation date of Selinus. Thucydides, an ancient historian, argues that it occurred around 627/8 BCE. However, other ancient historians, Diodoros and Eusebios, argue that it took place 242 years before it was destroyed by Carthage in 409/8 BCE, which would make its foundation around 650/651 BCE.

What is a Metope?

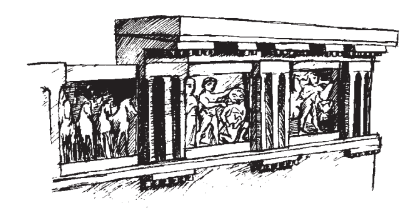

A metope is an architectural element of a Doric frieze. A Doric frieze is a decorative band or panels on a building made up of metopes and triglyphs. Metopes are typically located between two triglyphs, which are vertically channeled tablets. The metopes themselves are usually sculptures or paintings. Some of the myths depicted on Temple C’s metopes include Herakles and the Cercopis, Perseus and the Gorgon, the Orestes and Clytemnestra, and the Chariot of Apollo.

Historical Context

When was Temple C and its Metopes Built?

Only a few metopes from Temple C survive today in an almost entirely reconstructed form; however, many other metopes fragments from other parts of the temple are also available for investigation. Temple C’s metopes date to the middle of the sixth century BCE. The reconstructed metopes were made of limestone and rested on the eastern facade of the temple. The temple itself was constructed around the middle of the sixth century; however, there is some controversy over whether the metopes have an earlier or later character than the temple. An argument for the early character of the metopes is based on their seemingly early architectural style, but the metopes’ early character could also represent the colonial city’s provinciality.

Condition of Temple C and its Metopes Today

Temple C itself is currently in ruins; however, several of its metopes are in the museum in Palermo, Sicily. Although the metopes VII, VIII, and X are from the eastern facade of the temple, it was likely that the metopes wrapped the entire temple and were destroyed over time. Several other sculpture fragments from the temple show a second chariot group in one of the metopes, along with fragments of a bearded head, three female heads, a male torso, and several other sculpture pieces.

Cultural Relevance

Where was Temple C and its Metopes Located?

Temple C and its metopes were in the main urban sanctuary within the southeast sector of the Acropolis. Selinus was also home to several other temples, all referred to with letters of the alphabet. Temple C was built on the site of the old megaron, a kind of great hall, and was the largest building in the Acropolis. It was a monumental peripteral temple of the Doric order, with six by seventeen columns and a cella. A peripteral temple is a temple with columns on all four sides. It faced the east and had a large flight of stairs, enhancing its effect as an awe-inspiring monument with a dramatic entrance. The eastern side of the building had several different metopes sculptures. These sculptures depicted mythological subjects – Herakles and the Cercopi, Perseus and the Gorgon, and the Quadriga, or chariot, of Apollo.

How do the Metopes fit into the Overall History of Sicily’s Greek Art and Architecture?

The taste and style of Greece heavily influenced Sicily’s art and architecture. Sicily’s artistic productions were made to match Greek aesthetics, and by doing so, a bias towards a colony’s place of origin can be seen in their relationships to workshops in Greece. These styles may have also become intertwined with many aspects of local interpretations and styles. Selinus was home to a school of sculpture working during the sixth and fifth centuries. This also speaks to the importance of art and architecture in the lives of the Selinuntines and the colonists’ desire to have their Greek culture present in their homes through this medium. The building of Temple C took place around a century after Selinus’ foundation and is the earliest surviving temple on the Acropolis. The designs of these specific metopes were popular with Greek builders since the beginning of the Doric Order; however, the metopes were deeply innovative because of their introduction to plasticity and the balanced optical corrections that required the viewer to see the metopes in a specific manner. While looking at the metopes straight on the figures seem awkward because of their proportions, but they were designed that way to be viewed from a higher angle while on the side of the temple. The frontal poses and high relief of the sculptures in Temple C created the impression of material apparition.

Who was the Temple and its Metopes Built for?

Because the founding colonists of Selinus were from Megara-Hyblaea in Sicily and Megara-Nisea in Greece, our understanding of the monument changes because of the identity of the people for whom the metopes were created. The people from Megara-Nisea specifically would have wanted art pieces that reflected Greek deities and culture. While there was most likely a prominent Greek culture in Megara-Hyblaea, because those colonists had already settled in Sicily, their culture could have blended with the native Sicilian culture in some ways. Moreover, Selinus’ location in the west of Sicily meant that it had to rely on relationships with surrounding peoples who were non-Greeks. This included the Sikels, the Elymians, and the Carthaginians. Selinus’ peaceful existence was reliant on their relationships with these groups. These relationships, specifically with trading, may have contributed to the vigorous and inventive nature of Selinus’ artistic development. The creativity of this growing art in Selinus is exceptionally apparent in Temple C’s metopes.

Why are the Metopes Unique and How do they Connect to Other Architecture?

Something particularly interesting about the study of the metopes of Temple C is that the thematic interpretation of its metopes is located in the public dedication found in Temple G. Temple G is one of the other ancient temples located in Selinus. This inscription lists the gods to whom the Selinuntines are offering thanksgiving for victory. In order, the gods are: Zeus, Ares, Heracles, Apollo, Poseidon, the Dioscuri, Athena, Malphoros (Demeter), and Pasicrateia (persephone). These gods are also all depicted on the metopes. According to Ross Holloway, these metopes are an “epiphany of the Selinuntine pantheon.” This comparison makes sense because both the Pantheon and the metopes use depictions of the major divinities of their cities as a form of functional art. The metopes serve to materialize the deities and to create a presence of the Greek gods in the colonists’ new homes. Although Temple C was dedicated specifically to Apollo, the metopes’ interpretation of all of the Gods of the city represented the temple not as a singular unit, but connected to the religious life of the entire city.

Discovery and Excavation

Who Discovered and Excavated Temple C and its Metopes?

The metopes of Temple C were discovered and excavated in 1823 by two British architects of the Royal Academy of Arts in London: Samuel Angell and William Harris. Harris and Angell’s investigation into the temple and its metopes occurred at an interesting point in time. Greece had not emerged from its war of independence with the Ottoman Empire, and Temple C’s metopes were the first kind of early archaic Greek sculpture introduced to Western Europe. These metopes hold an interesting point at the beginning of the rediscovery of archaic Greek art and architecture and the Western world’s infatuation with ancient history.

Some controversy lies in Angell and Harris’s original excavation of the metopes. The two researchers did not officially ask for permission to clear the debris. Angell and Harris excavated the site despite laws prohibiting private research. After discovering the metopes, Angell and Harris made a formal request to Naples for permission to display the metopes to the British Museum, at the same time sending the metopes to the house of a British vice-consul in Mazara for restoration. Local authorities in Sicily halted the movement of the metopes to Mazara and demanded they be sent to Palermo. A few months later, after Angell had died of malaria, Naples denied the researchers’ request that the metopes be sent to the British Museum and ensured that they were housed in a museum in Palermo, where they remain today.

Analysis of the Metopes

East VI: The Second Quadriga

This metope is one of two confirmed representations of a quadriga, or chariot. As Metope East VI is the better preserved of the two, it has been the subject of much discourse regarding its mythological identification. The frontal chariot is agreed to be reminiscent of war, and the lack of armor equipped on the charioteer suggests that the central figure of the quadriga is a god rather than a mortal man. Similarities to another, smaller metope on Temple C suggest that this metope may depict the sun god Apollo being greeted by his mother, Leto, holding a wreath off to the side. While other interpretations have been proposed, the quadriga undeniably inspires awe for the incredible craftsmanship and mythological presence within the metopes.

East XII: Perseus and Medusa

Metope East XII depicts the mythological event of the Greek hero Perseus slaying Medusa. Perseus stands in the center, holding his sword against Medusa’s neck. To his left stands Athena, one of the prominent patrons of Perseus. Some unique iconographic elements in this metope are the front-facing figures, the lack of wings or snakes on Medusa, and the young Pegasos. In most two-dimensional carvings and paintings of Greek myths, the figures represented all face to the side, Medusa being an exception to emphasize her deadly gaze. However, this metope and others identified on the temple depict multiple front-facing figures. The difference may heighten the sculptures’ impact on viewers as if the mythical figures emerge from the stone.

The depiction of Medusa in this metope also differs from standard iconography. A monster called a “gorgon,” Medusa is usually characterized by wings and snakes around her head; however, these traits are absent here. Still, her fearsome facial features and beheading make her unmistakable, along with the key symbol of Pegasos. The creature Pegasos, a winged horse, is commonly associated with Medusa as myth dictates that it was born either from her severed head or the mixing of her blood and the earth. Regardless of Pegasos’ specific origins, the creature is fundamentally intertwined with the death of Medusa.

East XIII: Heracles and the Kerkopes

Beside the Perseus and Medusa metope is Metope East XIII, which depicts the story of Heracles (also commonly known by his Roman title Hercules) and the Kerkopes. The Kerkopes were two brothers warned by their mother in their youth to beware of the “black-bottomed” man. Later in life, in their habit of thievery, the Kerkopes came across the mighty Heracles resting beneath a tree and conspired to steal his weapons. Heracles awoke with a start and wrangled the two brothers, tying them to a pole by their ankles and hoisting them over his shoulders. Upside down with their heads by his lower half, the Kerkopes realized that Heracles was the “black-bottomed” man they had been warned about, his thick, dark body hair a distinctive marker of the manly hero. In discussing their revelation, the Kerkopes amused the Heracles, and he let them go.

Some scholars argue that the design of the metope, with the Kerkopes suspended from their ankles with their hands bound to their chest, is reminiscent of small animals retrieved in a hunt. While the story is undoubtedly comical, it also emphasizes Herakles’ strength over his “prey.” Indeed, the term Kerkopes has etymological roots, meaning “the ones with tails,” implying the brothers are characteristic of animals.

Fragment East X: Orestes and Clytemnestra

The fragments recovered of Metope East X lead scholars to believe this metope depicted the killing of Clytemnestra by her son Orestes. One portion of the metope shows the upper body of a seated woman, her hair being grabbed from behind. The woman’s seated position alludes to a characteristic of elevated social status, while the grip on her hair reflects the actions of an attacker with an intent to kill. Another fragment contains the legs of a man, which appear to be positioned in preparation to strike the seated woman. The fragmentation of the metope and less standardized iconography for the proposed myths makes identification difficult. However, many scholars agree that the relationship between the figures and the popularity of the Orestes and Clytemnestra myth makes this interpretation the most likely.

This metope represents a trend charted across Temple C through fragments and distinctly identified figures. In addition to famous heroes and traditional myths, much of the temple’s carvings present female characters relating to marriage, including wives, mothers, and virgins. These representations likely communicate a core value of the contemporary community. For example, Clytemnestra’s murder comes as a result of her taking a new lover and murdering her husband Agamemnon upon his return from Troy. Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, avenges his father by murdering Clytemnestra and her lover. The myth, then, inspires questions regarding loyalty, justice, and matricide.

Controversies

Controversies

Scholars have engaged in a few disputes over the content of certain metopes and the exact dates of their construction. Because many fragments of the metopes have been lost, certain scenes are nearly impossible to identify. Of those remaining fragments, disputes have attempted to confidently identify the intended mythological representations. One example is the Metope East X. While the theory of this metope as representing Orestes killing Clytemnestra is generally accepted now, many scholars disagree and still offer alternative theories. The metope was initially identified as Heracles killing the queen of the Amazons, but later investigations into the iconography suggest the Orestes-Clytemnestra interpretation. Other proposals include Menelaus and Helen, the sacrifice of Iphigenia, the death of Priamos, and others.

The time period of the metopes construction has also come under suspicion. Some scholars argue that the architectural style of the fabric on Perseus and Athena’s clothes in Metope East VII reflects a preference more common in works later than the Archaic period when most believe the Metopes were carved. The response to this claim suggests that, when engaging in routine maintenance of the metopes, this style was added later to “modernize” the temple decoration. This theory explains the identification of the metopes within the Archaic period while accounting for later design influences.

Bibliography

Bibliography

De Angelis, Franco. 2003. Megara Hyblaia and Selinous: The Development of Two Greek City-States in Archaic Sicily. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Guido, Margaret. 1977. Sicily an Archaeological Guide: The Prehistoric and Roman Remains and the Greek Cities. London: Faber and Faber Limited.

Holloway, R. Ross. 1991. The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge

Holloway, R. Ross. 1988. “Early Greek Architectural Decoration as Functional Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 92: 177-83.

Holloway, R. Ross. 1971. “The Reworking of the Gorgon Metope of Temple C at Selinus.” American Journal of Archaeology 75: 435-36.

Jannelli, Lorena. 2004. “Selinunte,” in Luca Cerchiai, Lorena Jannelli, and Fausto Longo (eds.), The Greek Cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily (Los Angeles, Getty), 256-267.

Marconi, Clemente. 2007. Temple Decoration and Cultural Identity in the Archaic Greek World: The Metopes of Selinus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rizza, Giovanni. 1996. “Siceliot Sculpture in the Archaic Period,” in G. Pugliese Carratelli (ed.), The Greek World (New York: Rizzoli), 399-413.