The Temple in Context

Syracuse, not to be confused with the university in upstate New York, is a city in Sicily, Italy. But this modern tourist destination actually has ancient roots. Thucydides, an Athenian historian, places its founding at 734 BCE. It began as a Greek colony, and it’s said to have been founded by an expedition from Corinth, a city-state in mainland Greece. Greek conceptions of colonization were quite different from modern conceptions, and at the outset, Syracuse was an independent state.

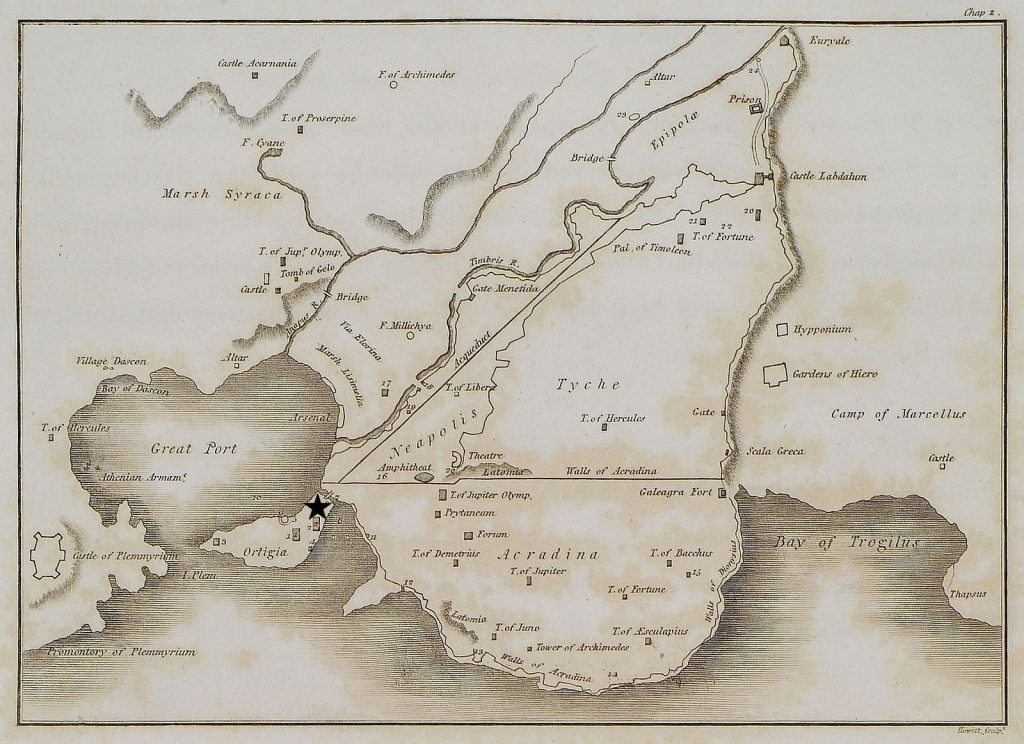

Syracuse is located in the southeastern corner of Sicily and was initially built on the small offshore island of Ortygia before later expanding to the mainland. Roughly 150 years after the proposed founding, they built the Temple of Apollo on Ortygia, near the mainland. This eastern-facing stone temple was a true monument. Apollo was the Greek god of archery, prophecy, music, and more. It was not uncommon that many of the Greek gods received temples within Ancient Greek cities.

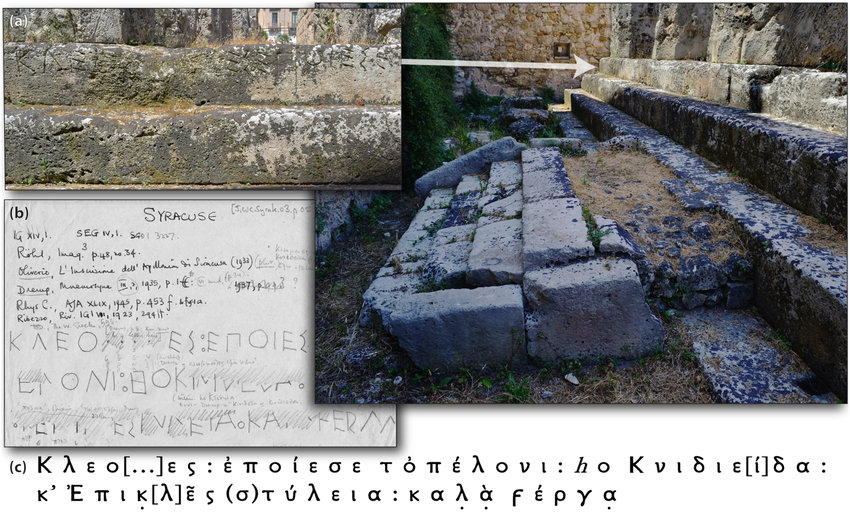

Inscriptions can be found throughout the Greek world. Often when someone wanted to dedicate something to the gods or have their deeds remembered, they would inscribe their words into stone. We are fortunate to have an inscription on the top steps of the Temple of Apollo; however, unfortunately, the inscription has been damaged over time. As a result of the damage, its translation has sparked much scholarly debate. A newer translation by Margherita Guarducci, a renowned classicist, is as follows:

“Kleomenes made [this] for Apollo, the son of Knidieidas, and raised the colonnades, beautiful works.”

Margherita Guarducci

Usually, the scholarly debate surrounds the role of Kleomones in building the temple: whether he was the tyrant of Syracuse at this time, an aristocrat who funded the construction, or an engineer who worked on the temple. Cutting-edge scholarship using 3D image reconstruction technology has found that Kleomones was likely an inventor who designed the tool for raising the 26-foot tall monolithic columns.

The Architecture

The Temple of Apollo at Syracuse is among the oldest examples of construction within the Doric Order, and one of the first instances of a Greek peripteral temple ever to be constructed entirely out of stone. Taken together, these three notable features of the temple, paired with its polychromatic (multi-colored) terracotta decorations, present us with a fine example of archaic Greek temple architecture—and key in the generation of classical modes of temple construction.

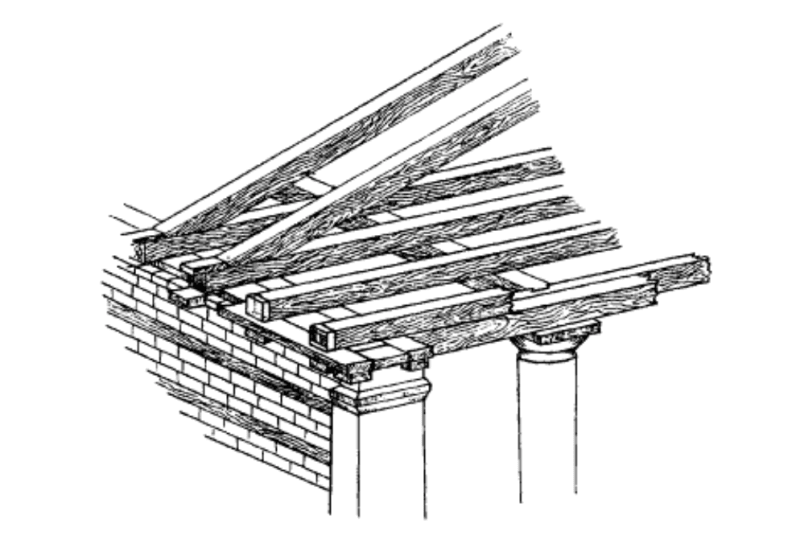

The lack of wood in the construction of the main part of the temple—excepting only in a few peripheral decorations along the ceiling—is notable not only for being among the first of its kind anywhere in the Greek world (having been constructed sometime around 600 BC), but for being the very first of its kind on the island of Sicily, and anywhere in the Western Mediterranean. The inscription at the foot of the Temple certainly emphasizes this, and the fact that such a stone-oriented manner of construction would quickly become the norm, not just in Greece, but in Italy and North Africa, attests to the cutting-edge nature of the temple and of its builder.

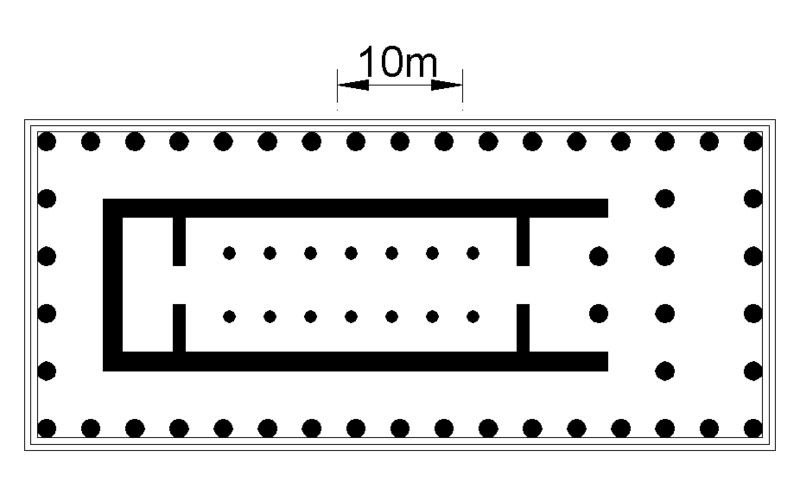

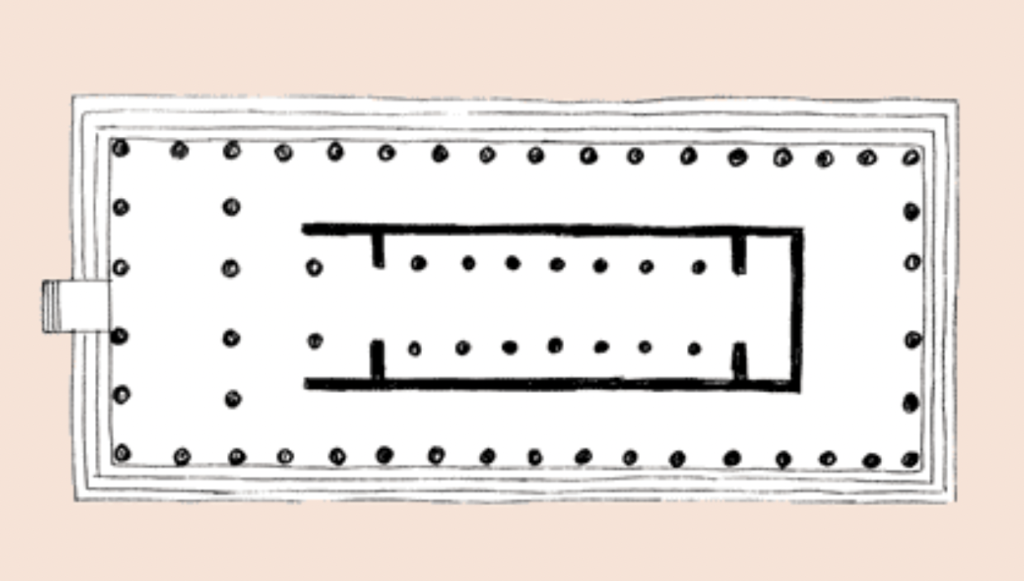

The novelty of stone construction in the Temple of Apollo is signified by three features in its design. Firstly, the columns supporting the temple are all placed extremely close together, so close that a man standing between any two of them could reach out and touch both with either arm. Secondly, the columns are monolithic—that is, each column is carved out of a single piece of Sicilian stone, and transported wholesale from the quarry in which it was mined. Thirdly, the porch of the temple, rather than being only a single column deep as is the norm with later peripteral structures, hosts two layers of tightly-spaced frontal columns. All three of these features evidence a nervousness concerning supporting a stone roof—a novel effort in that day.

The use of painted terracotta tiles on the roof, and the painting of the metopes along the exterior of the temple, both reflect a color palette of blacks, blues, reds, and creams which are common to Etruscan (Northern Italian) temple decor, and which would become the standard for Greek Doric temples going forward. Such a color palette and the contrasts involved would have made for an imposing, colorful, and eye-catching sight—the tallest stone building in Syracuse at the time, and certainly something to be seen from all about the early Syracusan city. This was certainly made all the more impressive by the fact that such tiles were likely among the first to be manufactured in Sicily.

Significance of the Architecture

Uncovering the Meaning Behind the Decisions

To reiterate the sheer significance of this feat, in order to construct the temple, the Syracusans would have required specialized quarrying, transportation, engineering, and work to erect the monolithic columns and raise its stone roof. Building this temple was clearly a concerted effort, requiring innovation and collective investment, and there was development of specific infrastructure to make this possible. Such an immense public building indicates the formation of the city that people would be willing to come together and invest their resources into its construction.

The architectural decisions can cause one to wonder if there are connections back to mainland Greece. By choosing to build in the Doric style, they are displaying that although they are a truly independent colony, there still exist kinship ties back to Corinth. The Dorians are one of the major ethnic groups in Greece, mainly located on the Peloponnesian peninsula, which houses Sparta and Corinth. As a result, the Syracusans still see a connection with this ethnic group in choosing to build in its style. Additionally, while many Greek temples faced east, due to the positioning of Sicily, this temple faced east towards mainland Greece and to Corinth, further suggesting potential ties back; however, this very well may be due to coincidence.

If you have viewed a Greek temple, you may have realized that they are quite long. Often Greek temples are twice as long as they are wide. This temple is even more elongated at more than twice its width. Thinking geometrically, an elongated rectangle does not maximize internal area, as squares have the maximum area in proportion to their perimeter. This potentially is not beneficial to the priest who would spend time inside the temple; however, an elongated rectangle does actually maximize the side profile, which may have magnified the sense of wonder in spectators.

The temple featured the symbol of the Gorgoneion on its front, likely on its triangular pediment (or on the metopes). This symbol portrays the head of the gorgon. Most notably, this symbol occurs in the story of Perseus when he beheads Medusa. The symbol of the Gorgoneion is said to have warded away supernatural evil and discouraged religious crimes. Furthermore, as feelings of fear and anxiety were common for worshippers to experience in their encounters with the sacred, the Gorgoneion must have served to compound these overwhelming and mysterious feelings. It must have been also deeply unsettling for Greeks, as it depicts the gorgon looking forward, while contemporary Greeks would have been almost exclusively portraying figures’ profiles, yet this gorgon was looking straight at them.

Change and Continuity

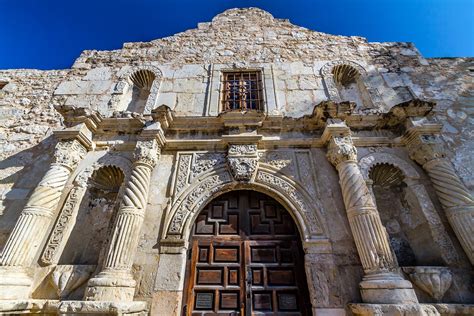

The Temple of Apollo remained standing for well over a thousand years in one form or another. Having remained a functioning Greek temple all the way until the onset of Roman rule in Syracuse, the Temple, likely looted during the infamous governance of Verres, nevertheless stayed in use up to the point of being converted into a Catholic church during the waning years of the Roman Empire. It would remain a church until after the Muslim Conquest of Sicily, where it was briefly transformed into a mosque. When the Normans captured the city of Syracuse in 1086 AD, it was again turned into a Catholic church, renamed to “the Church of the Redeemer.”

A Church-turned-barracks that can’t be forgotten.

It continued to function in this manner until the Kingdom of Spain came into possession of the Two Sicilies, and transformed the church into a barracks—at this point, whatever remained of the temple was likely subsumed into the new structure of the superimposed garrison building. The barracks was eventually abandoned after the end of Spanish control in Southern Italy, and the Temple—no longer a visible, above-ground structure—was built upon and turned into what was functionally apartment housing.

In 1890, the Italian archeologist Paolo Orsi, finding the remnants of the temple’s columns within the barracks, oversaw the excavation of the temple site, and was responsible for turning the location into what it is today. The visible walls and columns of the temple stand still in the middle of Ortygia island, and a cella window, a memory of the temple’s near-thousand-year history as a Catholic church, is still standing and visible on the building’s remaining wall. While the site doesn’t allow tourists to walk about inside of the fenced-off ruins, it nevertheless remains visible without cost from the nearby roads and Syracusan farmer’s market.

Doric Greek Architecture

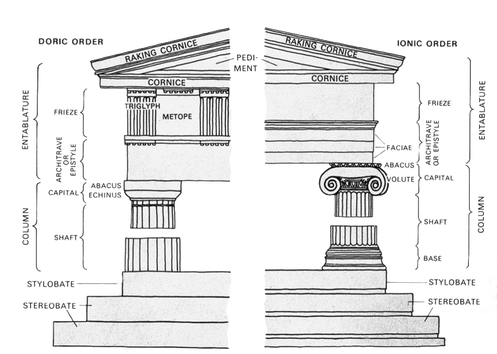

During the early part of the sixth century BC, around the time when the Temple of Apollo at Syracuse was built, certain schools (or “orders”) of architectural style began forming throughout the Greek world. While there arose a wide variety of these different styles, the Doric and Ionic Orders were the oldest and most common, and together with the Corinthian, they make up the three “canonical orders” of Greek temple architecture.

The Doric Order—originating from Doric Greek cultures located primarily in Peloponnesian—is often considered to be more simple, spartan (in both senses of the word), and “masculine” by architects working in the ancient world. The Roman writer Vitruvius, working in the first century AD, even comments on how, “the Doric column, as used in buildings, began to exhibit the proportions, strength, and beauty of the body of a man.” These features are often contrasted with the Ionic Order, which the same Vitruvius remarks as being “characteristic of the slenderness of women.”

The Doric mode is characterized by fluted columns (that is, columns with engraved “ridges” or grooves), which are topped with a plain capital and go down straight into the building’s foundation, lacking a base. These columns would often be wider on the bottom, and gradually grow more narrow as they rise. On average, Doric columns would be anywhere from four to eight times taller than the diameter, resulting in a comparatively “short and stocky” look, especially in comparison to the tall, thin columns of the Ionic Order.

Essential in most Greek temple construction, and pioneered in the creation of the Temple of Apollo at Syracuse, is the “peripteral” style. All Doric temples are constructed with a peripteros—that is, with the exterior of the building being entirely surrounded by columns which uphold a stone roof. Usually, this peripteros is a line of single columns that wraps all about the building. In the Temple of Apollo, however, there are two rows of front-facing columns: perhaps evidence of a kind of Etruscan inspiration, or of nervousness on the part of the architect in holding up the massive stone roof.

The use of triglyphs and metopes are also particular to the Doric Order, as the whole roof of the temple is wrapped around by interspersed three-line, carved decorations (triglyphs), and depictions of various mythological scenes or figures in relief (metopes). Seen adorning such temples as the Parthenon, such triglyphs and metopes are also featured prominently in the Temple of Apollo at Syracuse.

Bibliography

- Cerchiai, Luca, Lorena Jannelli, and Fausto Longo (eds.). 2004. The Greek Cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. Los Angeles: Getty.

- Holloway, R. Ross. 2000. The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily (London: Routledge Press), 54-74.

- Mertens, Dieter. 1996. “Western Greek Architecture,” in G. Pugliese Carratelli (ed.), The Greek World (New York: Rizzoli), 315-46.

- Miles, Margaret M. (ed.). 2016. A Companion to Greek Architecture. Malden: Wiley, 67-169.

- Pollio, Vitruvius. 1914. De Architectura. Trans. Morris Hickey. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

- Saperstein, Philip. 2021. “The First Doric Temple in Sicily, Its Builder, and IG XIV 1” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 90: 411-77

- Vecco, Marilena. 2007. L’ evoluzione del concetto di patrimonio culturale. (Venice: Universita Ca’ Foscari di Venezia).

- Zink, Stephan. 2019. “Polychromy, Architectural, Greek and Roman,” (Oxford: Oxford Classical Dictionary).