Overview

The Goddess of Morgantina, also known as the Getty Aphrodite, is a 5th-century BCE statue most famous for its unknown identity and origin, as well as being a stolen artifact from an excavation at Morgantina, Sicily in the late 1970s later sold to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California.

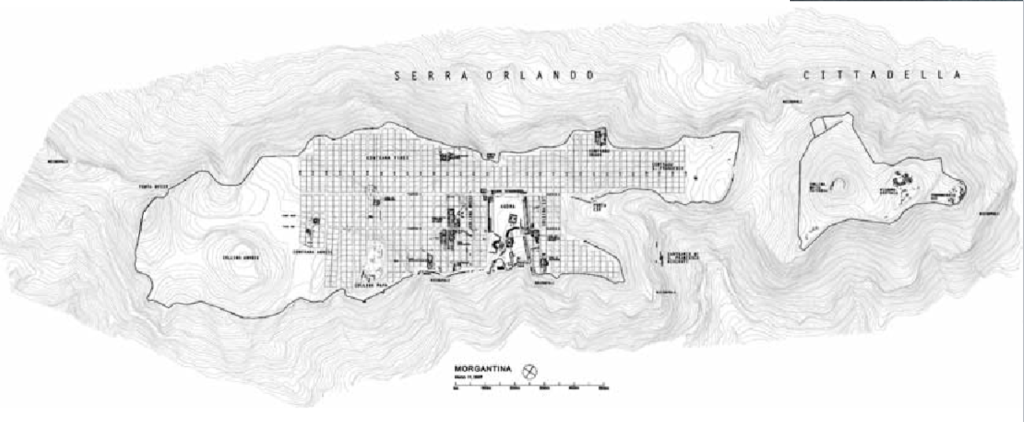

Morgantina had two distinct “eras”: the Archaic era found on Cittadella, and the Classical era on Serra Orlando.

In the Archaic time period, Morgantina had both heavy Indigenous and Greek influences, with both construction and artistic styles present in the city. For our goddess, we are looking at the Classical/Hellenistic era, where Morgantina was refounded after destruction in 459 BCE. At this point, Morgantina is looking like a very Greek city – it had a planned-out agora (public open space for markets and assemblies), a grid-like setup, and a theater.

Classical Morgantina was also home to a cult area for the goddesses Demeter, patron of agriculture and grain, and Kore, her daughter famous for her betrothal to Hades. This cult site was known as San Francesco Bisconti, and this is the most likely home for our goddess. However, it is complete speculation that she ever belonged there (for more info, check out our “Controversies” page!).

Details

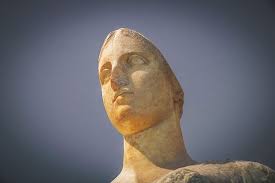

The Goddess of Morgantina stands at 2.20m tall. Her head and limbs are made of a mixture of Parian (from the island of Paros) marble, and her body is crafted from limestone taken from a Sicilian quarry. She’s missing an arm, and from broken texture on her shoulder, scholars assume that she likely was wearing a veil in her prime.

Our statue is sculpted in a style known as “pseudo-acrolithic,” defined by the materials used to create the sculpture. This style is almost always associated with cult statues of deities in or outside of temples. Further information from the statue is the remnants of red, blue, and pink paint which signals again towards her alleged purpose as a cult statue.

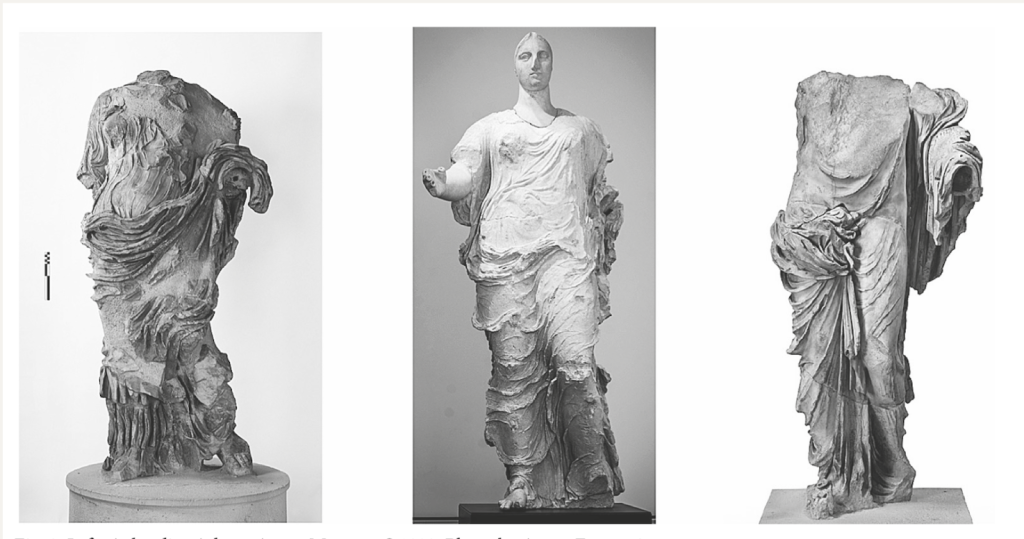

Noting the pseudo-acrolithic style, the goddess’s structure most closely matches the stylistic choices often attributed by 5th-century BCE Athenian sculptors. Below are two similarly dated statues of Aphrodite done by Athenians at the time, with our mystery goddess in the center!

By now, you certainly have noticed that we have not named what goddess is portrayed in this statue. That’s because no one actually knows the identity of the Goddess of Morgantina. Originally, she was thought to be Aphrodite, mostly because of the similarities above. The glaring contradiction that prevents identification as Aphrodite, however, is the lack of a low neckline on our goddess’s dress. This was a central attribute to works portraying Aphrodite at the time, so we can be pretty confident it’s not her.

So if it’s not Aphrodite, who is she? The three best options for identification are Demeter, Kore, and Hera, queen of the gods.

If we’re looking only at the goddess’s structure, we have a couple of key pieces of evidence for identification. For starters, in Greek art, the imagery of a woman with a cloak over her head represents marriage and maturity. Unfortunately for us, all three of our best options can be interpreted as either a matron, a wife, or both. Demeter, while never officially married, is heavily associated with being a mother due to her relentless search for Kore in her most famous myth. Along those same lines, Kore is most famous for her abduction and eventual marriage to Hades. Our final option, Hera, is both the ideal bride in her marriage to Zeus, and the mother of Hephaestus from her own creation and of Ares with her husband.

When attributes fail in identification, the next step is to look at mythology for any hints. Demeter and Kore are incredibly important to Sicilian culture. From Diodorus, an Ancient Greek historian active in the 1st century BCE (who is from Sicily!), Demeter gave the gift of agriculture to the Sicilian people first, and the famous Rape of Persephone myth occurred in Sicily, with Hades allegedly abducting her on the island and Demeter’s search for her daughter taking place all over Sicily. Tying this in with the best-guess site of the Goddess of Morgantina as a sanctuary for both Demeter and Kore, this fits pretty well!

So, why is it not a slam dunk to identify her as either Demeter or Kore? If you look closely at our goddess’s attire, she is wearing a chiton, a long rectangular piece of cloth draped as a tunic/dress, and is assumed to have had a himation, which is an outer garment draped over the left shoulder and tucked under the right. This is problematic for Demeter, since in Greek art she notably does not wear this attire. While Kore does, some scholars argue that the dress on our goddess has a “wind-blown” effect, which symbolizes promiscuity. Kore and Demeter are rarely, if ever, portrayed as promiscuous or sexual goddesses. Here’s where Hera enters. As previously mentioned, Hera is an ideal bridal figure as the bride of Zeus. She also has a promiscious history, and there are scholars who believe our goddess is portraying Hera’s most famous moment in the Iliad, in which she seduces Zeus to benefit the Greeks.

Those are just some of the facts attributing to the unidentifiable nature of our goddess. Who do you think she is?

Controversies

Probably the most iconic part of the Goddess of Morgantina is that she is covered in controversies. Here are two other sketchy situations our statue is a part of!

Lineage

This whole time, we have been referring to this statue as the “Goddess of Morgantina.” But, there actually is very little evidence that she is from Sicily, let alone Morgantina. Being honest, all we actually know is that the limestone used for the large body of the statue is from a quarry located between Syracuse and Ragusa, two city-states on the island.

So how was she attributed to the city of Morgantina? We fully have to rely on the testimony of the looters that stole this statue from Sicily, and they say that she was taken from Morgantina. Beyond their testimony, there have been various other famous stolen pieces found in Morgantina, like a head of Hades, so this statue could likely have been found there.

On our ‘Overview” page, we mentioned that the most likely home for our goddess is found in San Francesco Bisconti, at a cult site for Demeter and Kore. While this is the best theory we have, it also has holes in it. There are no sanctuaries or pedestals at San Francesco Bisconti, or in Morgantina at all, that could have housed a statue as large as ours. Plus, our goddess is from a period of economic transition in Morgantina, which makes it harder to believe that the amount of money needed to construct such a large statue was spent when she was constructed.

Wrong Head?

Yes, you read that right. When our goddess was stolen by the looters, she was cut apart into smaller pieces to make shipment easier. The body was cut into three pieces, and the limbs and head were also cut off and shipped separately. Since the body has that distinct Sicilian limestone, there was no concern about the validity of the body when the statue was put back together. However, scholars working at the Getty Museum believe that there is a good chance the head “belonging” to our goddess isn’t actually her head. When she was put back together, it was noticed that her head is weirdly smaller than her body when comparing the two proportionally. Her head also is not a snug fit on the rest of the body, which further draws into question if this head really is part of the original goddess.

Not only is the head questioned, but how the head got to the Getty Museum also has varying stories that lead us no closer to the true answer. One popular story about the Goddess of Morgantina’s head is tha the looters had put her head in a box, and had it shipped to Swiss border in the back of a carrot truck. This already sounds rediculous, but there actually is merit to possibly disproving this theory! Carrots are notably not native or popular in Morgantina, and based on the looter’s previous testimony about a stop in Gela, the route of going from Morgantina to Gela to the Swiss border would’ve had a lot of wasted time for such an in-demand head – shown below on a map of Sicily.

The other major conflict in the story of the head’s identity lies with the same city, Gela. Allegedly, Gela has 3 copies of the head from the original statue, but Morgantina also claims to have the real head.

Even though the head on the Goddess of Morgantina probably is not her original head, we can at least rest somewhat easy – art historians studying our goddess say that the head is at least an accurate representation of what the original statue would have looked like.

Legal Issues

This statue spent decades in the J. Paul Getty Museum, hence the nickname “Getty Goddess.” How she ended up in California is still largely a mystery, but here is what we know:

From Morgantina to Los Angeles

In 1977-1978, this statue was illegally excavated near the ruins of Morgantina (allegedly). That year, she was acquired by Orazio di Simone, an antiquity dealer.

In 1986, British art dealer Robin Symes purchased the goddess from Renzo Canavesi, a Swiss private collector, for $400,000. Later that year, Symes offered her to the Getty Museum for $18 million, saying all he knew was that the goddess used to belong to a Swiss collector.

Before purchasing the goddess, the Getty consulted several outside experts. Some of them were skeptical of the statue’s provenance, urging antiquities curator Marion True to turn down the offer. Iris Love, an American archaeologist, begged True not to go through with the sale, as it would only bring troubles and problems. Luis Monreal, the director of the Getty’s Conservation Institute, also advised against purchasing the goddess.

Regardless, the Getty Museum thought it best to keep the statue out of private collections. Before this purchase, the goddess had never been published or exhibited. In 1988, the Getty officially purchased the Goddess of Morgantina and were soon notified that an investigation was launched by Italian authorities on the statue’s acquisition.

The Getty would not hear more about the goddess’s history until 1996 when Canavesi offered more fragments. He claimed to be the former owner, explaining how his father brought the disassembled statue to Switzerland from France in 1939. Canavesi allegedly received the goddess in 1960, storing the parts in boxes until selling them to Symes. Five years later, Canavesi was found guilty in absentia for receiving stolen property.

The Goddess Goes Home(?)

In 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture reached an agreement with the Getty Trust. The museum was to return 40 objects to Italy, including the Goddess of Morgantina. Three years later, the statue was sent to Aidone, the closest modern town to the ruins of Morgantina.

What Went Wrong

So, which laws were broken? And who was charged with what? In 1989, Orazio di Simone was charged in Italy for illegal excavation and exportation of antiquities. He was believed to have sold the goddess to Renzo Canavesi, but the charges were dropped in 1992 for a lack of evidence. Canavesi was found guilty in absentia for receiving stolen property in 2001. He was fined the equivalent of $18 million. He also received a 2-year imprisonment sentence, which was appealed due to the statute of limitations period expiring.

Marion True, the Getty’s antiquities dealer at the time, also faced legal charges. In 2005, she was indicted for conspiracy to traffic in looted antiquities. She was accused of creating false evidence to obscure the goddess’s provenance, participating in a conspiracy through private collections. That year she resigned from the Getty, but her trial did not end until 2010, when the statute of limitations expired.

Today

The Goddess Today

Since 2010, the Goddess of Morgantina has stayed at the Aidone Archaeological Museum. The statue, its illegal excavation, and the Getty’s acquisition are now open to scholarship, continuing to spark debates among academics to this day. While the goddess is greeted by less visitors in Aidone than Los Angeles, she was warmly welcomed home by the local population. The Goddess of Morgantina was one of countless displaced antiquities, and her return to Sicily provides hope for other communities fighting to preserve their history.

Bibliography

- Bell, Malcolm III. 2007. “Observations on the Cult Statue,” in Mark Greenberg (ed.), Cult Statue of a Goddess: Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa (Los Angeles, Getty Publications), 14-22.

- Brand, Michael. 2007. “Introduction,” in Mark Greenberg (ed.), Cult Statue of a Goddess: Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa (Los Angeles, Getty Publications), 1-4.

- De Angelis, Franco. 2012. “Archaeology in Sicily 2006-2010.” in Archaeological Reports, 123-90.

- E-borghi (image of Aidone Archaeological Museum)

- Fraccaro, Elizabeth, et al. 2019. “Case Morgantina Goddess Statue – Italy and J. Paul Getty Museum.”

- Frederick Fisher and Partners (image of Getty Villa)

- Marconi, Clemente. 2007. “Acrolithic and pseudo-acrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess,” in Mark Greenberg (ed.), Cult Statue of a Goddess: Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa (Los Angeles, Getty Publications), 4-14.

- The Cultural Experience (map)

- Walsh, Justin St. P. 2011/12. “Urbanism and Identity at Classical Morgantina.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 56-57: 115-36

- Zisa, Flavia. 2017. “Art without Context: The ‘Morgantina Goddess’, a Classical Cult Statue from Sicily between Old and New Mythology. Actual Problems of Theory and History of Art. 169-178.