Overview

What is the Delphi Charioteer?

The Delphi Charioteer is a bronze statue depicting the victor of a chariot race at the Pythian Games, a series of athletic events held at the Sanctuary of Delphi in Ancient Greece. Instead of joyful in victory, the subject appears composed, strong, determined, and in control.

More questions than answers surround the Charioteer. Who is the victor? Who dedicated the monument and when? What is the meaning of the inscription associated with the statue? Years of historical speculation surrounding the monument have left us with few concrete answers. However, the statue still has historical significance in that it bears evidence of a distinct style of Greek sculpture (the “Severe style”) and may reveal important information about the Deinomenid tyrants of Ancient Sicily.

Details

Delphi, Home to The Temple of Apollo

Delphi consists of two ancient sanctuaries: The Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia to the south and the Sanctuary of Apollo to the North, which are both separated by the modern road. The Sanctuary of Athena includes the Temples of Athena and the Gymnasium is situated next to the site. The Sanctuary of Apollo includes the theatre, the Western Portico, the Stadium and the Temple of Apollo which comprised the Oracle of Delphi. The Greeks considered Delphi the religious center of the world since the oracle of the God Apollo spoke at the Sanctuary of Delphi. The “Sacred Way” describes the path leading to the Temple of Apollo. Greeks would dedicate wealthy offerings such as statues, figurines, or other objects to honor the God Apollo.

Delphi was also home to the Pythian Games, one of the four Panhellenic games. These games were second in importance to the Olympics and were held in Delphi once every four years to honor the God, Apollo. It was customary for winners to give votive offerings to Apollo as gratitude for their victory. The games were very central to the Greek tradition and played an integral role in asserting their culture.

Site plan of the sanctuary of Apollo in ancient Delphi (Laroche)

The Archaeological Site of Delphi

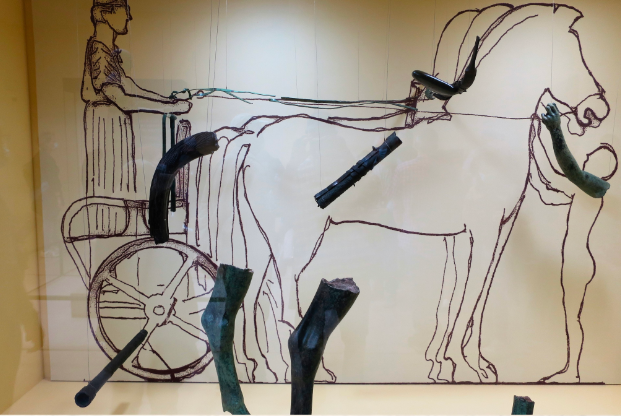

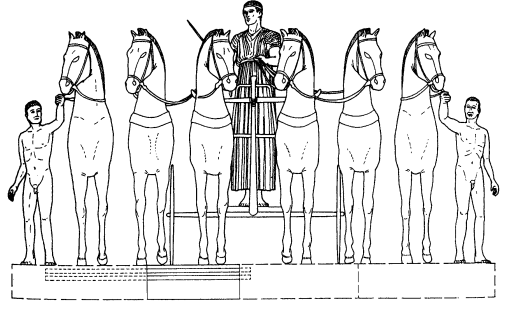

In 1891, the French Government set aside a large amount of funding for the excavation at Delphi with the support of the Greek government. After having been buried in an Earthquake in 373 BCE, the Delphi Charioteer was rediscovered by French Archaeologists in 1986 at the Archeological Site of Delphi. The Charioteer is presumed to be part of a much larger statue including a chariot being pulled by horses and stable boys by the sides. Findings of remnants of the horse’s legs help to visualize the larger picture.

The monument is now housed in an exhibit at the Delphi Archeological Museum located adjacent to the Archeological site.

Artistic Style

Sculptor and Artistic Style

The Delphi Charioteer was constructed by Greek sculptor, Pythagoras, in the late fifth century. The statue is composed of a bronze body, copper lips and eyelashes, onyx eyes, and silver teeth and headband. The charioteer primarily consists of bronze, and was constructed with bronze casting using the Lost Wax Method. The Lost Wax Method involves the sculptor initially creating a full scale wax model and covering it in clay. Then, the sculpture is heated to melt and remove the wax and molten bronze is poured into the cavities in replacement of the wax.

This monument is an exemplary model of the Severe Style of art which spanned the from 480BCE – 450BCE, marking the transition from the Archaic Period to the early Classical Period of art. The archaic style of art was characterized by naturalism, focusing on human figure and motions and the Classical Period was characterized by realism, which focused on accuracy, detail, and portraying figures in a realistic life-sized manner. The Charioteer reflects the transition from Archaic to Classical periods as the body.. The patterns of the charioteer’s xystis follow a more ideal geometric pattern resembling Archaic art whereas the facial features are defined and precise resembling the artwork of the Classical Period.

Stylistic Comparisons

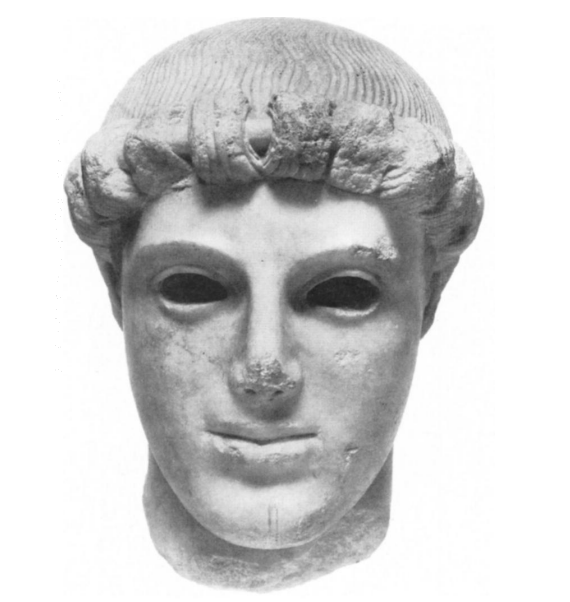

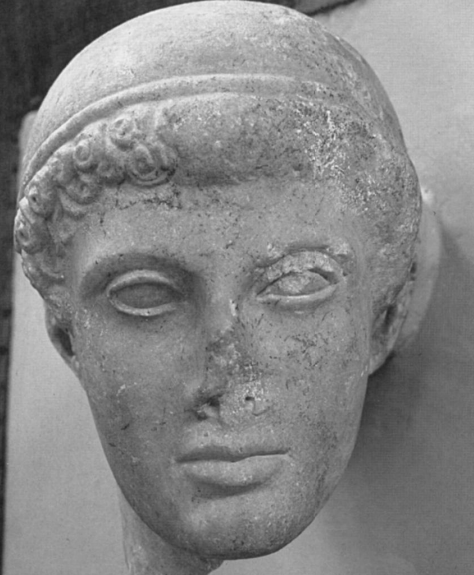

Stylistic comparisons between the Charioteer and other ancient Greek monuments have led to further conversations about the style and the dating of the monument. One popular comparison for the Charioteer is the Kritios Boy which is a severe style monument of the early Classical period (480-470BCE). While there are differences in appearances of their bodies with the Kritios Boy is naked and the Charioteer is wearing a xystis, their heads have been the focus of comparative analysis. While there are some similarities such as the shape of their heads, their facial details and hair details differ greatly on closer examination. The Charioteer’s nose and eyebrows are carefully defied, representing a realistic expression, whereas the Kritios Boy’s features are more square and blocky. It is important to note that some of these differences in facial traits could be due to the use of stone as opposed to bronze. A more accurate resemblance is between the Charioteer and the Head of Athena (470-465 BCE) from the metope at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The realistic facial features as well as defined smaller curls of the hair on the Head of Athena closely resemble those of the Delphi Charioteer.

The Delphi Charioteer (c. 480-450 BCE); Located at the Archeological Site of Delphi, Delphi

The Kritios Boy (480-470 BCE); Located at Acropolis, Athens

Head of Athena (470-465 BCE); Located at Temple of Zeus, Olympia

Inscription

Inscription

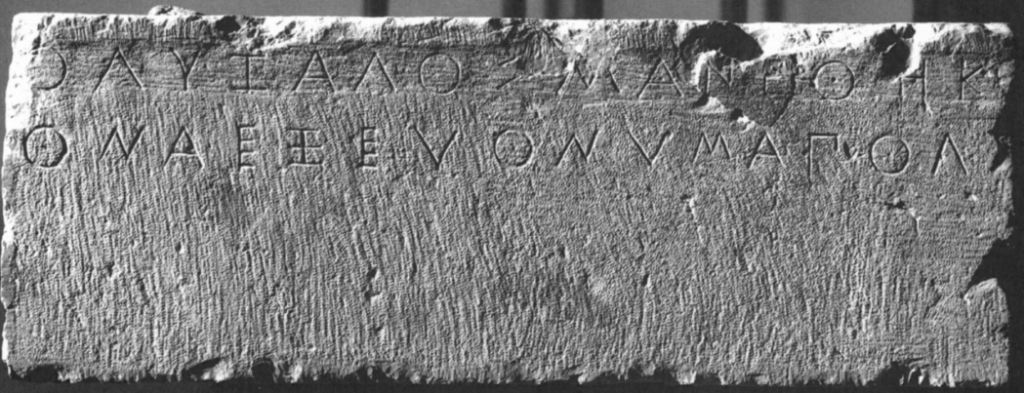

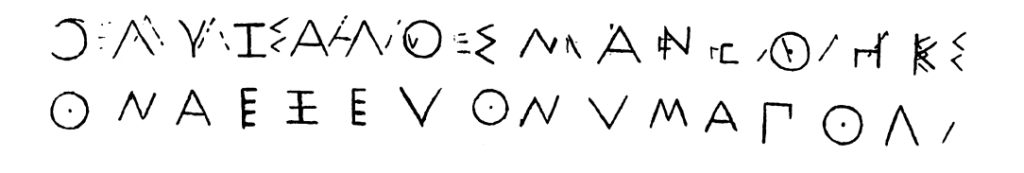

The only inscription connected to the monument is found on an artifact known as Base 3517, which was recovered near the statue. The base bears evidence of two inscriptions, the first of which was later edited to include the name of Polyzalos, a member of the Deinomenid family of Sicilian tyrants.

he, being ruler of Gela, dedicated / give him glory, noble Apollo

Initial Inscription

The base refers to a ruler of Gela, which historical consensus seems to indicate was Deinomenid brother Hieron, the only of the brothers to have had a recorded chariot victory at the Pythian Games.

Polyzalos dedicated me / give him glory, noble Apollo

Edited Inscription

The edited inscription attributes the statue’s dedication to Polyzalos. It is known that the relationship between Polyzalos and Hieron was fairly rocky, as the former plotted to overthrow the latter in 476 BCE. Some sources indicate that Polyzalos desired a position of greater authority under Hieron. This revision to the inscription could be an act of self-promotion, or a play for power.

Present Condition and Controversy

Discovery and Present Condition

The Charioteer itself is only in partial condition. The monument was separated from its hypothetical limestone base during an avalanche at the Sanctuary of Delphi which occurred following an earthquake in 373 BCE. Only small portions of the base, the chariot, and the horses and stable boys remain.

Controversy and Base 3517

Much of the major controversy surrounding the monument has to do with the inscription recovered on base 3517, which was assumed to be one quarter of the statue’s original base. This controversy arises both from the initial association of base 3517 with the actual statue, and the muddled translation of the writing on the artifact by one of the original archaeologists, Théophile Homolle.

The commonly accepted reconstruction of the historical and artistic backgrounds of the celebrated Charioteer of Delphi statue rests on a delicate chain of reasoning connected with the inscription on a base block from the sanctuary

Gianfranco Adornato

Recognizing the name of Deinomenid brother Polyzalos on the base, Homelle’s original translation incorporated theoretical lines of text which pointed to the statue being a dedication to Polyzalos’ older brother Gelon, who was known to have funded chariot racing at athletic games across Greece. Ultimately, Homelle’s translation is a fantasy and cannot be supported by historical evidence. It has since been replaced by the two translations referenced in the inscription tab of this website.

Any claims about the origin of this statue rely on such a tenuous connection with base 3517 that all proposed interpretations should be considered with a grain of salt. Given the fact that the statue and the base were recovered separately, and in the midst of a landslide which destroyed many other monuments along the Sacred Way at Delphi, it is largely impossible to determine that the two are actually both part of the same artifact.

Bibliography

- Adornato, Gianfranco. 2019. “Kritios and Nesiotes as Revolutionary Artists? Ancient and Archaeological Perspectives on the So-Called Severe Style Period.” American Journal of Archaeology 123: 557-87.

- Adornato, Gianfranco. 2008. “Delphic Enigmas? The Γέλας ἀνάσσων, Polyzalos, and the Charioteer Statue.” American Journal of Archaeology 112: 29-55.

- “The Archaeological Site of Delphi.” Archaeological Museum of Delphi. https://delphi.culture.gr/.

- Holloway, R. Ross. 1991. The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge.

- Lunt, David. 2022. The Crown Games of Ancient Greece. Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press.

- “Selected Exhibits: The Charioteer.” Archaeological Museum of Delphi. https://delphi.culture.gr/museum/selected-exhibits/.