Overview

The Theater at Syracuse is a large ancient Greek theater located in the city of Syracuse (Siracusa) on the eastern coast of Sicily. After nearly five centuries of rule by Greek-speaking city states, eastern Sicily had become firmly entrenched in broader Greek culture, and was a key player in ongoing cultural, artistic, and political trends.

In prior periods, performances of the arts (such as tragedies, comedies, music, and dance) were typically held in open-air settings, sometimes on temporary wooden stages. But by the Hellenistic period (323-31 BCE), elaborate stone complexes dedicated to hosting public performance were being built all across the Greek world, and indeed, the Theater at Syracuse is very much in line with this trend, sharing a similar layout to other Hellenistic theaters across the Mediterranean.

Not only is the theater a good representation of how tightly Sicily was linked into the rest of the Greek world of the time, but also as we will see, it gives substantial insight into how the construction of public works often served as a tool for rulers, in this case Hieron II, to fortify their positions of power.

Layout

Features

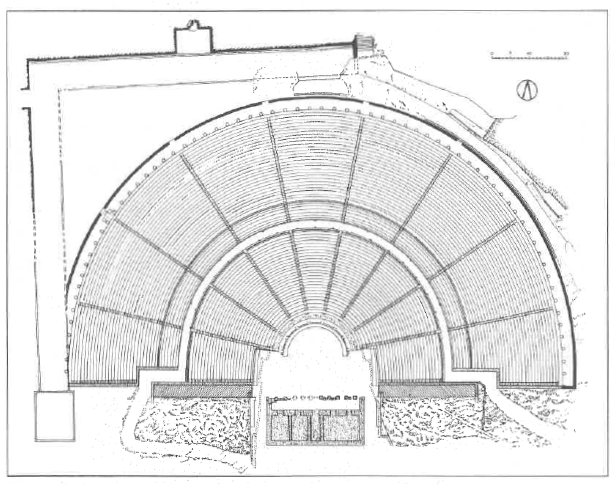

Most of the theater was carved directly into the south face of Temenite Hill, though in antiquity, much of its structure was also built up from this as well.

The theater was, at its core, a typical example of a Greek-style theater for its time. It consisted of a large horseshoe shaped seating area, 130 m in diameter, consisting of 67 rows which belonged either to an upper or lower tier. Both tiers were further divided into nine wedges. In total, this was estimated to carry up to 15,800 people. Between the upper and lower tiers was an arcing walkway called a diazoma.

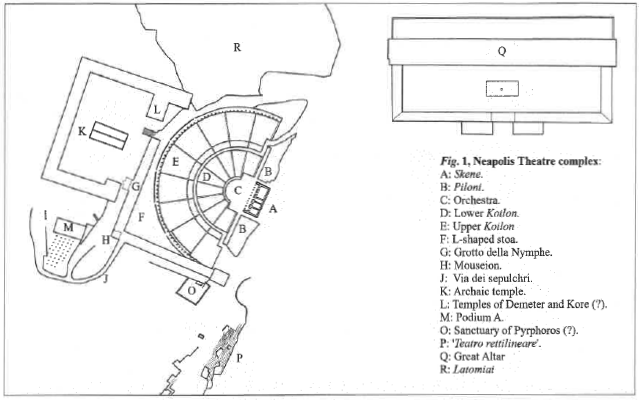

At the base of the seating was a circular mainstage called the orchestra which was used for speeches and monologues because of the way it allowed a speaker’s voice to carry throughout the theater. Behind this, at a slight elevation was a two-story building called the skene which not only served as an ornate backdrop to performances, but also contained backstage green rooms. Directly in front of the orchestra was a single row of seating, meant for honored guests and dignitaries. At the front of the theater, on each side were pathways 25.5 m long and 3.5 m wide called prohedrai, each with an arch over the entranceway. This is where all attendees, performers, or orators would enter and exit the theater.

Surrounding Complex

In antiquity, numerous buildings accompanied the theater. Surrounding the seating area were temples to the Gods Apollo, Demeter, and Persephone, as well as a Mouseion where gifts and offerings from other cities could be displayed. Also nearby was the Great Altar, a massive building meant to host the ritual sacrifice of dozens of cattle at once. Built at the same time as the theater and in a similar style, it was the largest building of its kind in the ancient world, measuring in at 198 m long.

Behind the theater the Grotto delle Nymphe, an artificial expansion of a natural cave. Out of its mouth, a stream of water from a subterranean aqueduct fed into the temples and the Altar.

Construction and Purpose

Historical Context

All that remains of the theater dates to the late 3rd century BCE during the reign of Hieron II (308-215), the tyrant-king of Syracuse who had the theater constructed as part of a public works project. Hieron ruled parts of south-eastern Sicily during the Hellenistic period, and shortly after his death, the Romans took over the entire island, finally capturing Syracuse in 212 BCE.

Historians and archaeologists are unsure whether a theater existed on site before Hieron remodeled the whole area. Any structure which was there beforehand would have been carved into during the remodeling, making it difficult to tell if the theater predates Hieron or not. Though some literary sources mention a theater existing prior to Hieron’s time, scholars do not take these to be conclusive evidence since most were authored long after his death, sometimes several centuries later.

What is known to predate Hieron are some of the temples surrounding the theater, some of which show archaeological evidence of ritual offerings dating back to as early as the 7th century BCE, shortly after initial Greek settlement of the area.

Purpose of its Construction

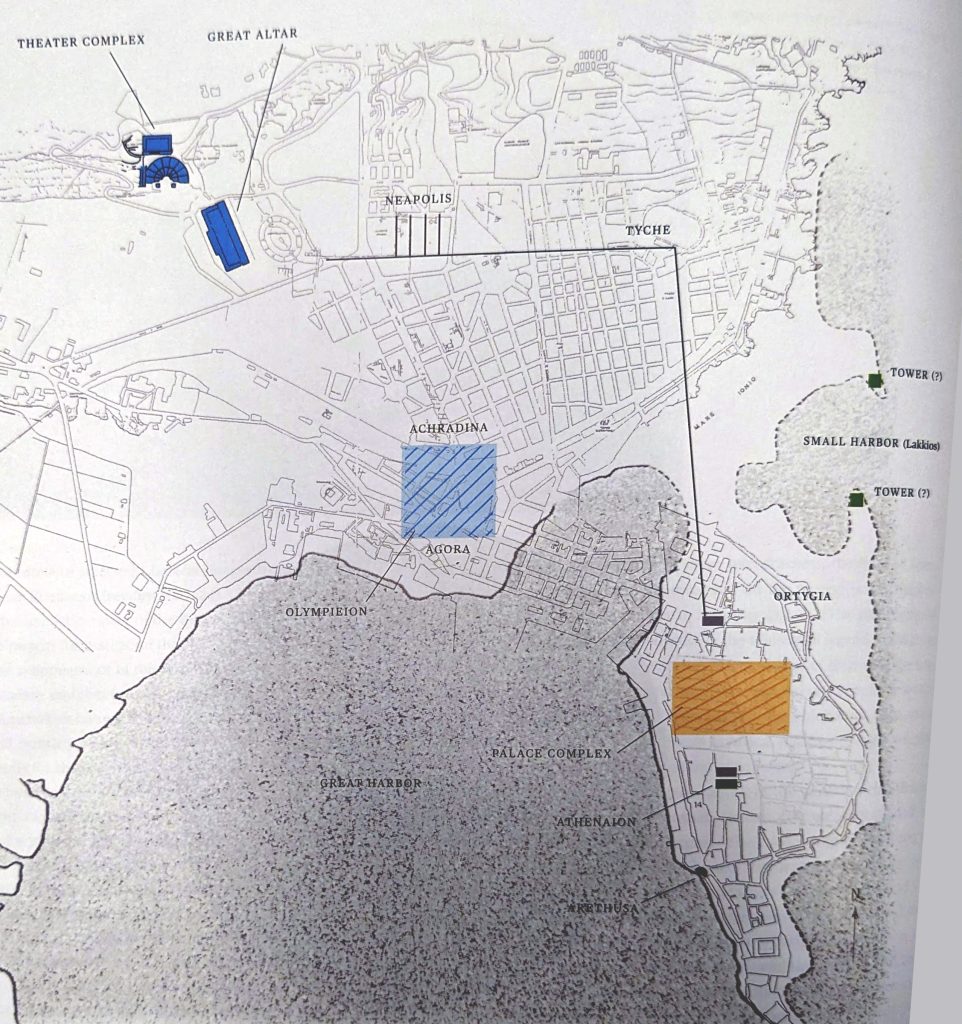

Scholars speculate that Hieron funded this public work primarily as a tool for propaganda, and that from the very beginning it was built for political purposes. For one, the theater was built in Neapolis, a section of Syracuse which was located at its north-west outskirts. This allowed it to be easily accessed by both city-dwellers and country folk. Hieron may have chosen this location with the intention of fostering a sense of unity among his subjects, specifically with his rule as the underlying factor holding it together.

Second, a Greek city’s theater was typically its most important public site, serving as an embodiment of local civic pride. It is likely that Hieron decided to renovate the whole complex and build a grandiose and modern theater in his signature “Hieronian” architectural style because this would lead the public to believe that it was his leadership which allowed such a great public work to be built.

The skene was large and highly ornamented, with stone busts of mythical figures (maenads and satyrs), and a lion fountainhead which was solely decorative being the only surviving examples. As well as representing the nature-vs-civilization imagery, this tells us that the structure was made to be permanent, literally set in stone, meaning that the people could praise Hieron for his generosity even long after his own death.

Public Uses

While a modern audience might tend to think of a Greek theater as being primarily intended to host public productions of tragedies and comedies, scholars and archaeologists actually believe that the main function of this theater was to act as a place of public assembly, and that its use as a venue for the performing arts was secondary.

Although democracy was no longer practiced in Syracuse, Hieron could still use it as a place for public addresses and speeches which his subjects could all rally around. While it is likely that the arts were still performed there, this is not mentioned by any writer of antiquity. Instead, all references to the theater at Syracuse in literature show it being used as a public space for the masses to gather.

Inscriptions and Texts

Mentions in Antiquity

There are only very few definitive literary references to this site during antiquity, and all are from centuries later. The most detailed description comes from Plutarch (ca. 46-119 CE), a Greek philosopher and historian who wrote the following in his biography of beloved Sicilian statesman Timoleon:

“[T]he proceedings in their assemblies afforded a noble spectacle in [Timoleon’s] honour, since, while they decided other matters by themselves, for the more important deliberations they summoned him. Then he would proceed to the theatre carried through the market place on a mule-car; … And when [his] opinion had been adopted, his retainers would conduct his car back again through the theatre, and the citizens, after sending him on his way with shouts of applause, would proceed at once to transact the rest of the public business by themselves.”

Plutarch Life of Timoleon 38

This is set during a time of democracy in Sicily, before Hieron’s reign, and we see there that Plutarch presents the theater as being a place where citizens gather to vote on public matters.

Other sources include Diodorus of Siculus (1st century BCE), a Greek historian from Sicily, who mentions the theater offhand. Again, it is seen as a place for the public to gather:

“ … and at dawn the whole people flocked to the theatre even before the archons had made their customary proclamation.”

Diod. 16.84

Cicero (106-43 BCE), a Roman statesman and scholar, also describes the theater in brief detail:

“ … on the highest point of this stands the great theatre ; besides which there are two splendid temples, one of Ceres [Demeter] and the other of Libera [Persephone], and a large and beautiful statue of Apollo Temenites …”

Cic. In Verrum 2.4.119

Inscriptions

In the seating area, along the back wall of the central diazoma, there were nine total inscriptions, one for each wedge section of seating. Only six of them survive to the modern day:

[βασιλέος Γέλωνος] // [Of King Gelon]

βασιλίσσας Νηρηίδος // Of Queen Nereis

βασιλίσσας Φιλιστίδος // Of Queen Philistis

[β]ασιλ[έος ʻΙέρω]νος // Of King Hieron

Διòς ᾿Ολυμπίου // Of Zeus Olympios

[—] // [—]

[ʻΗρ]ακλέο[ς κ]ρατε[ρό]φρονο[ς] // Of Herakles Kraterophron

[—] // [—]

[—] // [—]

These inscriptions acted as labels for each of the seating sections, possibly for the purposes of assigned seating. Each label relates to either a revered God or a member of Hieron’s royal family. Hieron, his wife Philistis, and his son Gelon (also called ‘King’) and his wife Nereis are all mentioned. The inscription of Hieron’s name is positioned at the righthand side of the inscription of Zeus’s name as if to signal that Hieron is the ‘right hand man’ to Zeus. All of this served as a very public reminder that Hieron and his family were favored by the Gods, giving them a divine right to rule over Syracuse.

Today

A Theater in Ruins

Nowadays, many features of the theater are in ruins or are missing entirely. During the Roman period, the theater was still in use, and the front row seats (prohedrai) were removed, as well as part of the diazoma wall, thereby connecting the upper and lower seating segments. During this time, the Romans also added other structures nearby, including the Anfiteatro Romano, an amphitheater used for gladiatorial matches and horse racing.

During the middle ages, the theater fell into disuse, and between 1576 and 1921, water mills led to the intentional digging of drainage basins, causing the water to erode part of the soft bedrock. Later, during Spanish occupation in the 16th century, much of the building material was repurposed elsewhere, leaving only the foundations of the skene and stage, the lower half of the seating, and only trace remnants of the surrounding temples.

New Life

In the modern day, since the 1920s, restoration efforts have sought to protect and preserve the theater and the surrounding area, now called the Neapolis Archaeological Park. Nowadays, every summer, the performance school INDA (Istituto Nazionale Dramma Antico) retrofits the site with a modern stage and seating and holds live productions of ancient Greek plays for a public audience, including those of Sophocles and Aeschylus.

Bibliography

Sources Cited

- Boardman, John, José Dorig, Werner Fuchs, and Max Hirmer. 1967. Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Bosher, K. G. 2021. Greek Theater in Ancient Sicily. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cerchiai, Luca, Lorena Jannelli, and Fausto Longo (eds.). 2004. The Greek Cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. Los Angeles: Getty.

- De Lisle, Christopher. 2023. “The Autocratic Theater of Hieron II,” in Eric Csapo et al. (eds.), Theater and Autocracy in the Ancient World (Berlin: De Gruyter), 55-69.

- Holloway, R. Ross. 1991. The Archaeology of Ancient Sicily. London: Routledge.

- Veit, Caroline. 2013. “Hellenistic Kingship in Sicily: Patronage and Politics under Agathokles and Hieron II,” in Claire L. Lyons, Michael Bennet, and Clemente Marconi (eds.), Sicily: Art and Invention Between Greece and Rome (Los Angeles: Getty Museum), 27-36.

Web Resources

- INDA: https://www.indafondazione.org/en/

- UNESCO: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1200

- Lonely Planet synopsis: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/italy/sicily/syracuse/attractions/parco-archeologico-della-neapolis/a/poi-sig/471856/360014

- Park tickets and description: https://aditusculture.com/en/esperienze/siracusa/musei-parchi-archeologici/parco-archeologico-della-neapolis